Adaptation of a Couple-Based HIV Intervention for Methamphetamine-Involved African American Men who have Sex with Men

Abstract

In the U.S., incidence of HIV infection among men who have sex with men (MSM) has steadily increased since the 1990s. This points to a need for innovation to address both emerging trends as well as longer-standing disparities in HIV risk and transmission among MSM, such as the elevated rates of HIV/STIs among African American MSM and methamphetamine users. While couple-based sexual risk reduction interventions are a promising avenue to reduce HIV/STI transmission, prior research has been almost exclusively with heterosexual couples. We sought to adapt an existing, evidence-based intervention—originally developed and tested with heterosexual couples—for a new target population consisting of African American MSM in a longer-term same-sex relationship where at least one partner uses methamphetamine. The adaptation process primarily drew from data obtained from a series of focus groups with 8 couples from the target population. Attention is given to the methods used to overcome challenges faced in this adaptation process: limited time, a lead investigator who is phenotypically different from the target population, a dearth of descriptive information on the experiences and worldviews among the target population, and a concomitant lack of topical experts. We also describe a visualization tool used to ensure that the adaptation process promotes and maintains adherence to the theory that guides the intervention and behavior change. The process culminated with an intervention adapted for the new target population as well as preliminary indications that a couple-based sexual-risk reduction intervention for African American, methamphetamine-involved male couples is feasible and attractive.

INTRODUCTION

Following a decrease in HIV incidence in the U.S. during the earlier decades of the epidemic, transmission has plateaued at about 56 thousand new infections per year [1, 2]. The limited decrease in HIV incidence during recent years highlights a need for continued vigilance as well as novel preventive intervention programs. However, the plateau in overall incidence belies a concern particularly for men who have sex with men (MSM): not only does male-to-male sexual contact continue to represent the major conduit of HIV transmission in the U.S. (53% of all new infections and 72% among male cases in 2006) [2], but inspection of the data reveals that incidence rates for MSM have been increasing steadily since the 1990s [1].

The need for sexually transmitted infection (STI) risk reduction among MSM stems not only from a shared risk behavior (e.g., sex without barrier protection), but also because the physiological and immunological sequelae of STIs can fuel the transmission of HIV [3]. There has been a recent increase in incidence of STIs among MSM [4], who are already overrepresented among STI cases. In New York City (the locale for the current study), annual rates of major reportable STIs have increased since 2005 [4].

Innovative approaches to sexual risk reduction are needed to counter the aforementioned trends in HIV and STI transmission among MSM. While MSM clearly shoulder a large burden of the HIV epidemic, epidemiological research strongly points to additional subpopulations of MSM with elevated rates of HIV infection in the U.S.: African Americans [4-6], methamphetamine users [7, 8], and men in longer-term (vis-à-vis casual) relationships [9, 10]. That smaller subpopulations carry a proportionally higher load of the HIV epidemic has led to recommendations to focus prevention efforts on populations at highest risk for infection as a “pressing public health and humanitarian imperative” [11]. It is possible that unique dynamics are leading to higher rates of infection among these populations. For example, the likelihood of unrecognized HIV infection may decrease as main partners transition into longer-term partners (or vice versa), but the presumably lower risk may be offset by a higher frequency of unprotected receptive anal intercourse and fears that introducing condom use would elicit mistrust or suspicions/acknowledgement of extradyadic partners [9]. Another possibility is that past/current prevention (and outreach) efforts are not resonating or consonant/compatible with the context in which these individuals live, especially for those at multiple risks. Altogether, these considerations prompted formative work to develop a novel behavioral sexual risk reduction with content tailored for those at the nexus of populations at elevated risk for HIV and STIs: African American men in longer-term, same sex intimate relationships in which at least one partner is using methamphetamine (herein referred to as “African American, methamphetamine-involved male couples”).

Couple-Based Interventions for Sexual Risk Reduction: Meeting the Need for Innovation

Despite being the largest group of HIV-infected individuals, MSM have fewer population-specific HIV interventions with scientific evidence of efficacy reported in the scientific literature as of 2002 compared to other major risk categories [12, 13]; this situation does not appear to have changed substantially if at all [14]. While a growing body of evidence underscores the promise of a couple-based approaches in promoting sexual risk reduction among populations at elevated risk for HIV [15], the focus has been almost exclusively on heterosexual couples. No couple-based interventions specifically for MSM have been identified in meta-analyses and systematic reviews of HIV preventive intervention trials with stronger scientific design (e.g., randomized clinical trial) [16, 17]. Couple-based HIV/STI prevention directly addresses the elevated risk among MSM in longer-term relationships as noted above and may bring innovation to renewed reductions in HIV transmission among MSM.

A couple-based approach may also be particularly useful strategy for engaging individuals who have been out of reach of the prevention outreach and health services system. A couple-based approach can start with recruitment of the partners of hard-to-reach individuals; in our experience, the partners often want the difficult-to-reach individual to engage in services and positive behavioral change, and the partners can be very compelling in recruiting/engaging the hard-to-reach individuals because of the conjoint delivery of the intervention [18]. Thus, a couple-based approach can start with recruitment of MSM who are not methamphetamine users, but who may be in an intimate relationship with a methamphetamine user who is not currently engaged with services.

A Starting Point: The Connect HIV/STI Preventive Intervention

The Connect intervention, a couple-based HIV/STI sexual risk-reduction for mixed-gender couples, has been demonstrated to be efficacious at 3-months and 12-months post-intervention [19, 20] and has been selected for inclusion in the CDC’s Compendium of HIV Prevention Interventions with Evidence of Effectiveness. The 6-session Connect intervention combines content related to safer sex practices and prevention of HIV and STIs, with an emphasis on sexual communication and negotiation skills. The intervention cultivates responsibility and ability to protect oneself, one’s intimate partner, and fundamentally, one’s intimate relationship. The process is facilitated by a focus on a positive future orientation and risk reduction as a sign of caring, as opposed to focusing on past risky behavior and condom use as a sign of mistrust. The intervention also works to empower participants to act as health advocates who are enhancing the future well-being of communities hardest hit by HIV/AIDS.

Revision of the Connect intervention in order to be delivered to African American, methamphetamine-involved male couples naturally involves scrutinizing content that reflects an assumed relevance and/or central importance of potentially heteronormative content (e.g., knowledge of female anatomy, traditional gender norms); however, it may be equally heterocentrist to assume that such information is irrelevant for all male couples. These concerns, their underlying considerations, and the concomitant challenges are exacerbated by the dearth of information in the empirical knowledge base regarding relationship and couple-dynamics among men of color in longer-term, same-sex relationships. HIV prevention researchers have put forth models for rigorous, formal adaptation of existing interventions for new target populations [21, 22]; these can be multi-stage endeavors that impose considerable requirements on time, resources to evaluate/compare existing evidence-based interventions, dedicated staff to collect new information and implement revisions, and existence of multiple knowledgeable experts on the new target population. However, communities have pressing needs that may benefit from swifter progression in developing promising interventions. Furthermore, community-based organizations may not have the information, technology and staffing resources to evaluate a number of existing evidence-based interventions, or an agency may be structured/staffed to deliver a particular intervention [for a different target population]. Furthermore, for hidden or disenfranchised populations, there may be an inadequate level of existing knowledge or few experts, especially if the problem is emerging. These constraints were in place with respect to sexual risk reduction for African American, methamphetamine-involved male couples. Thus, we endeavored to develop and implement an adaptation procedure that seeks to maintain a high level of scientific rigor in the face of these challenges.

METHODS

Design

Obtaining in-depth, contextual information regarding the risk and protective factors and dynamics among African American, methamphetamine-involved male couples was accomplished using qualitative methods, i.e., focus groups., with couples from the target population. Given the very limited existing research on couple-based HIV prevention with male same-sex couples, especially MSM of color, we felt that holding a series of focus groups with the same couples would be more efficient at covering a large number of issues/topics in greater depth than the alternative of multiple focus groups with different couples. Thus, couples were asked to return and participate in up to six focus groups. Earlier focus groups were designed to elicit participants’ worldviews and experiences about the challenges African American, methamphetamine-involved male couples experience regarding general well-being, methamphetamine use, and HIV risk/protection. Later focus groups presented existing intervention activities and study protocols in order to solicit and elicit participant feedback and ideas on how to enhance the relevance, engagement, and safety for risk reduction behavior change among African American, methamphetamine-involved male couples.

The Institutional Review Boards of the funding agency and the investigative team’s institution approved all protocols, materials, and information used in this study. All participants provided full informed consent prior to the focus groups.

Sample

Individuals and their partners were eligible to participate in the focus group if they both met the following eligibility criteria:

- Be male identified;

- At least 18 years old;

- Report having a “primary main male partner” operationalized as:

- a male with whom he has had an ongoing sexual relationship over the prior 6 months,

- a male with whom he has the intention to remain together with for at least 12 months, and

- a male with whom the participant has an emotional relationship/bond more than any person;

- Self-identify as African American and/or Black, or identify having a main partner who self-identifies in this manner (Note: for multiracial participants, they must state their primary race/ethnicity is “African American” or “Black” to be eligible);

- Have had unprotected anal sex with a man who is a non-main partner in the past 2 months (or, regardless of awareness, has a main partner who meets this criterion);

- Report using methamphetamines at least once in the past 60 days (or, regardless of awareness, has a main partner who meets this criterion);

- Reports not being either in or seeking drug treatment (in-patient, out-patient, support groups, AA, etc); and

- Identifies each other as their main partner.

Many of these criteria have been used and/or are analogous to the investigative team’s prior HIV intervention research studies with [heterosexual] couples, drug-involved couples, and African American couples [19, 23] except for the following: eligibility criteria 3c and 7 were agreed upon and used by all of the sites participating in the Cooperative Agreement that provided funding for this study. Since the intervention is designed to be delivered conjointly to both members of a couple, an additional requirement was that both partners had to be willing to attend the focus group together.

Procedures

Recruitment

Recruitment was conducted in a variety of manners. “Active” methods included study staff conducting outreach and recruitment activities at local service agencies, bars, clubs, commercial and public sex environments, and community events frequented by MSM and located in the multiple neighborhoods and boroughs of New York City. “Passive” referral was also used, whereby referrals were made through local agencies and organizations that provide programs and services for methamphetamine-involved, minority MSM (e.g., AIDS service organizations, health clinics, dental clinics), project community advisory board members, current participants, and individuals/couples who screen out of other ongoing studies but who may be eligible for this study.

If study staff recruited/contacted only one member of a couple who may be eligible, that individual was asked to invite his main [male] partner to participate. Potential participants were given a letter addressed to their partners that introduces the study, describes its purpose, describes reimbursement for participation, and contains a contact telephone number. Only after a partner contacted study staff would any recruitment, screening, or enrollment procedures be initiated with that partner. In no case did study staff share any information provided by the first individual to his partner.

Focus Groups

All focus groups were held in a private room at the research institution. The co-facilitators—the lead author who is the Principal Investigator of the study and the Project Director who was an African American MSM—followed a semi-structured interview guide constructed for each of the six focus groups. Focus groups were held weekly and lasted 90-120 minutes. They were audio recorded and one or two note-takers from the study staff were also present. Each participant was compensated $40 (i.e., $80/couple) for his time and information.

Since this report is focused on the adaptation process, qualitative data and themes presented in this article have been selected based on their relevance to the adaptation process. Space constraints prohibit providing verbatim or detailed description of qualitative data related to more general matters regarding the experiences of African American, methamphetamine-involved MSM in longer relationships; we have endeavored to present such information in other venues [24, 25] as well as in a separate, forthcoming manuscript.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the Study Sample

A total of eight couples participated throughout the focus groups with the target population. Two of the couples were recruited via referral from local service providers; the remaining couples were recruited by outreach staff over six recruitment outings conducted in the evenings and lasting about 3-4 hours each. The age of participants ranged from 29 to 48 years old (mean = 42.3 years). All but three of the participants identified as African American/Black; one interracial relationship was with a Caucasian (European-American) and the other two interracial relationships consisted of an African American and a partner who identified as biracial (African American/Latino). Six of the couples consisted of only one partner who met the methamphetamine use criterion, though it became apparent that the other partner in many of these couples had used methamphetamine in the past. Only 1 of the couples had accessed/received any services together as a couple (couples therapy).

Across the six focus group meetings, only two couples missed a single meeting. Of those two meetings where an entire couple was missing, one was planned due to a prior engagement and only one was an unanticipated “no show.” In one other instance, one participant attended while his partner could not due to a planned prior engagement. All other couples were willing and succeeded in attending scheduled sessions [together].

Adaptation Process

Eliciting Information Needed for Adaptation

The focus group co-facilitators followed an interview guide that contained a series of open-ended questions designed to elicit participants' worldviews, experiences, and understanding/insights in four primary areas: (1) influence of methamphetamine on sexual risk behavior; (2) core components of the intervention; (3) barriers to participation in an HIV preventive intervention study; and (4) ethical issues. A separate guide was created for each focus group such that earlier group meetings tended to have a greater proportion of questions designed to elicit data on experiences and worldviews among the couples, and later groups focused more on obtaining feedback on intervention activities/content. Table 1 presents some example interview guide questions for each of the four areas. In addition to sharing their experiences and perceptions, participants were prompted to respond to each other’s comments and/or indicate agreement/differing opinions. Finally, as a topic was concluding, participants were often asked, “What about other couples you may know?”

Sample Questions from the Focus Group Interview Guide

| Methamphetamine and Sexual Risk Behavior |

|

|

|

| Core Components of the Intervention |

|

|

|

| Barriers to Study and Intervention Participation |

|

|

|

| Ethical Issues |

|

A Relationship-Oriented Ecological Framework Applied to Sexual Risk Behavior Among African American, Methamphetamine-Involved Male Couples

| Ontogenic Level |

|

|

|

| Microlevel |

|

|

|

| Exolevel |

|

|

|

| Macrosystem |

|

Social Cognitive Theory Constructs in the Context of Couple-Based Intervention for Behavioral HIV Risk Reduction

| Information/Knowledge |

|

|

|

| Outcome Expectancies |

|

|

|

| Social and Self-Regulatory Skills |

|

|

|

| Self-Efficacy |

|

|

|

| Social Support |

|

Capturing Lived Experiences of African American, Methamphetamine-Involved Male Couples

The paucity of research on African American MSM in longer-term same-sex relationships, combined with the recognition that literature on methamphetamine use among African American MSM is limited compared to other populations, prompted a significant amount of focus group questions and time to be dedicated to collecting background and contextual information about the lives of African American, methamphetamine-involved male couples. The process of eliciting, analysis, and inference about the experiences and worldviews was guided by a relationship-oriented ecological perspective [26]. This couple-based, multi-level framework organizes the broad range of proximal and distal factors that shape human behavior and interpersonal relationships. Furthermore, by characterizing the different analytic levels of organization as nested, the relationship-oriented ecological perspective acknowledges that factors reciprocally interact and influence each other both within and across analytic levels. Table 2 lists the analytic levels and examples of specific factors within each analytic level posited to shape the lives—including HIV/STI risk and protective behaviors—among African American, methamphetamine-involved male couples.

The ontogenetic level refers to the personal factors that are unique to one’s developmental history and experiences. One prominent theme was how the level of comfort with identity, sexuality, and presentation were shaped by earlier life experiences, particularly rejection or acceptance of non-heteronomativity among one’s family of origin. Several participants described growing up with families located in southern regions of the U.S. and more heavily involved with religion as negative experiences themselves. Another topic noted by many focus group participants was the sexualizing and sexual stereotyping of African American men. When asked to discuss methamphetamine use, the psychological disinhibition, cognitive dissociation, and physiological effects were thought to reflect a means of coping with prevalence of sexual difficulties (both psychological and physiological) that arose and/or varied depending upon the different levels of accepting/rejecting experiences.

The microlevel consists of the interactional and structural factors that are part of the immediate intimate relationship context in which sexual activity and risk and protective behaviors take place. By far the most noted and discussed were the impact of differences between partners. Frequently mentioned areas of differences between partners included: experiences of being accepted/rejected by family (e.g., “We are constantly comparing our childhood.”); level of comfort being “out” as an individual and in an intimate relationship with each other; past sexual experiences; and use of drugs and or stage of recovery. While these differences were often focal points of difficulties/disputes in the relationship, participants noted how methamphetamine use and sexual behaviors [that increase HIV risk] could be a means to cope or address the differences. For example, attending or arranging a methamphetamine and sex party was noted as a solution to the desire to connect sexually with one another, despite being fully aware of risk of disease transmission and/or the potential paradox arising from sexual non-monogamy. The microlevel also encompasses a noted dynamic of how a partner who is not HIV-positive nor using drugs/methamphetamine is “left out while he [the HIV-positive/methamphetamine using partner] gets the attention [of service providers and programs].”

The exolevel refers external stressors or buffers on the relationship and likelihood of engaging in risky behavior. A common theme was how intimacy and interaction with one’s partner was impacted and often undermined by social settings and community-level factors, most of which could threaten the quality and sustainability of the relationship itself. For example, many participants noted or described a hypervigilance about being seen as non-heterosexual and not being able to show affection towards their partners in public, mostly mentioning places around their residence and work (e.g., “I would want to give him [partner] a kiss, but he would lean away and say ‘No, this is where I live.’”). Of particular note was several participants noting that African Americans may be less likely to live in historically gay-friendlier sections of New York City. Methamphetamine use was noted to be a means to connect with other MSM as well as a occurring in safer places/venues where they could be intimate with their partner. Interestingly, one participant did note that in contrast to seeing gay-friendlier neighborhoods as predominantly white, there was a more recent trend of African American non-heterosexual youth congregating in such areas presenting an image they did not want to be associated with (e.g., “Those homothugs you see in Chelsea, I can’t stand that.” “Those homothugs aint ever going to amount to nothing.”). The same participant suggested that this provided an answer when his associates would ask, “Why you use that white boys’ drug?”

The macrosystem encompasses the broad cultural values and belief systems that shape and interact with all of the other analytical levels. Participants noted that the centrality of family and religion they felt was prominent among African Americans often exacerbated the rejection and stigma originating from their family members. The spectrum of responses to such dynamics among focus group participants varied: some felt they had reconciled, many were still struggling, others accommodated (selective passing, “don’t ask, don’t tell”), and some rejected and/or disenfranchised themselves from those social institutions.

This range of responses underscores the importance of the investigative team’s deliberate choice to use of an anti-racist framework in considering macrosystem factors. The anti-racist ideology rejects “race-” or “color-blind” rhetoric; instead, the approach is to recognize, acknowledge, and address the varied lived experiences and perceptions among different races/ethnicities [27]. The anti-racist framework may be optimal for the following reasons. First, rather than needing to achieve expert understanding of African American/Black experiences, the approach is to foster participants to understand, analyze, and share the impact of race for themselves. Second, it does not seek to impose or presume a unifying framework upon African Americans (e.g., the Afrocentric paradigm or Afrocentricity [28]); because African American MSM may experience disenfranchisement from families of origin (e.g., “Being gay, my mother and father hated me.”) and/or the African American communities (e.g., “We [gay men] are not accepted in the Black community.”), we felt was important to provide for a wider range of worldviews to be expressed, explored, and acknowledged. The anti-racist perspective expands upon notions of cultural competence and cultural humility [29] by explicitly paying attention to race-based power, privilege, and oppression. Such issues can not be ignored as they underlie the social and structural factors that drive the health disparities, such as HIV, shouldered by African Americans. Finally, the anti-racist perspective also accommodates the varied phenotypes that may be represented among partners as well as the service providers and researchers working with the target population. Paralleling the anti-racist perspective, we pose and employ an anti-heterocentrist ideology; this perspective affirms and accepts different sexual identities and labels (especially those beyond gay and bisexual), which is particularly relevant given the attention paid to non-gay identities and labels for same-sex behaviors (e.g, “down-low”) among African American MSM. Some participants stated they identify as gay and/or homosexual, some embraced subverting the derogatory nature of the term “faggot,” and others noted referring to themselves or others as a “snow queen” or “Carlton.”

Participants were also asked to reflect on lived experiences to explore possible candidate “scenarios” used in intervention activities. Scenarios thought to have high relevance by participants regarding couple conflict/communication/ problem-solving include: “the call”—whereby an individual does not follow through on a promise or agreement to calling his partner if he was staying out/coming home late, going to drink or use drugs, etc.; not following through on abstaining or refraining from drug/methamphetamine use; and drugs/ methamphetamine during sex with each other. Participants also endorsed activities that encourage/enhance communication about sex, sexual desires, inhibitions, and their possible origins (e.g., “the baggage makes free-flowing discussion about sex difficult”). Participants shared about conflicts about sex arising from [lack of] top/bottom versatility, whether sex is spontaneous or planned, watching pornography, and being intimate without intercourse. These types of information were incorporated into role-plays and areas for intervention facilitators to explore during sessions.

Applying a Theory of Behavior Change

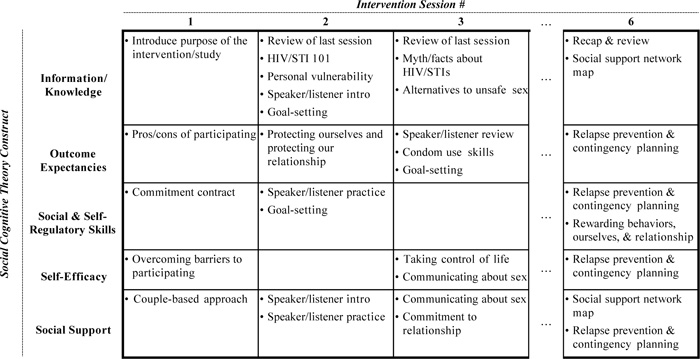

Beyond experiences and worldviews, analysis of focus group data needed to focus on how to enact risk reduction, specifically putative mediators of behavior change targeted by the intervention. The original Connect intervention was guided by Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) [30]. Thus, intervention activities are designed to increase the following among participants in order to enact risk reduction behavior: information and knowledge that underlie accurate appraisal of risks and risk behavior; outcome expectancies, which are perceived costs and benefits of certain behaviors; social and self-regulatory skills to recognize triggers of risk and enact risk reduction, including reinforcement of health-promoting behaviors; self efficacy, which is belief in one’s ability to implement desired or chosen behaviors; and social support, which refers to reciprocal interpersonal influences that increase, decrease, or sustain certain behavior and behavior patterns. Table 3 presents examples of how these SCT mediators are targeted in the context of couple-based HIV risk reduction for methamphetamine-involved couples.

Deconstruction and Reconstruction of the Intervention

Adapting an existing intervention with multiple sessions, whereby each session also contains multiple exercises, presents a challenge due to the sheer number of activities that must be systematically and strategically revised. We developed a visualization tool—the Deconstruction/ Reconstruction Matrix—that captures the essence of adapting a theory-driven intervention. One dimension of the tool’s matrix is the session number, while the other dimension is the theoretically posited mediators targeted by the intervention. Each activity/element in a session is then placed in the matrix based on the session during which the activity takes place as well as the mediator targeted by that activity. Fig. (1) depicts the essential structure and sample elements for the Deconstruction/Reconstruction Matrix for the original Connect intervention.

Example of a Deconstruction/Reconstruction Matrix used for the adaptation of the Connect intervention. Bulleted items represent activities conducted during the indicated session.

The Deconstruction/Reconstruction Matrix not only enhances identification and tracking of all intervention activities, but also helps ensure adherence to the theory behind how the intervention enacts behavior change. To adapt the Connect intervention, the matrix helped to make sure that the revised activity hit the same targets/mediators, with changes to information, content, and presentation that was more appropriate and compelling. For example, focus group participants’ suggestion of using direct language for sexual orientation (e.g., “gay”) instead of using a “generic” phrase like “men who have sex with men.” This was further refined by the anti-heterocentrist macrosystem understanding, culminating with the intervention having facilitators asking for and using the identity label that the participants prefer.

Of note is that some activities may show up multiple times in the same column of the matrix, indicating that some activities target multiple mediators. By intentional design, some sessions also do not have activities that target certain mediators. We also acknowledge that there may be activities that do not fit into the matrix (e.g., welcoming activities, graduation ceremony). Such activities may be related to clinically important issues such as engagement and termination; however, if the target of an activity is not or can not be determined, this may indicate that the purpose may need to be clarified, offering another opportunity to strengthen the intervention via revision or deletion.

Adaptation of an existing intervention for a new target population may be strengthened by the addition of new activities into the intervention. New activities might be focus on issues and dynamics that have been overlooked or not play as significant an impact for the original target population compared to the new target population. For example, focus group participants suggested that sexual histories figured prominently in shaping sexual behaviors and communication among African American MSM. Thus, we added an activity—the “Couple Timeline”—designed to elicit more detailed sexual histories from participants and provide an interactive, visual presentation of the temporal sequence of event. Participants stated that this new activity allowed both partners to gain a greater appreciation and awareness of the impact of each of their personal histories in a more meaningful, interactive manner than the activities in the original intervention. Placing new activities into the Deconstruction/Reconstruction Matrix helps ensure that new/added activities are consistent with the theory that guided the original intervention, which is SCT for the Connect intervention. We then examined other intervention activities originally constructed before/without the Couple Timeline, and incorporated revisions that could leverage the information elicited or presented in the Couple Timeline activity (e.g., aligning drug use history with sexual history to foster insight on outcome expectances related to drug use and sexual [risk] behavior). Thus, additional passes through the matrix are possible and were performed as activities are added and consequently revised. The visualization tool also minimizes the chance that some mediators may inadvertently receive insufficient attention due to accommodating new activities or revisions.

Altogether, the adaptation process involved deconstructing the original intervention into component activities, each activity revised in a manner that adheres and promotes theoretical rigor, and then reconstructed. Comparing the matrix for the original intervention versus the matrix for the revised intervention provides a quick means to visualize the adaptation.

Ancillary Activities

Additional developmental activities focused on adapting and revising materials used for engagement, recruitment, and retention. Participants were also uniformly enthusiastic about the appeal and potential promise of a couple-based intervention for African American, methamphetamine-involved male couples. A prominent theme involved countering the experience of invisibility and isolation of African American MSM couples (e.g., “We’re an endangered species…Show two Black men as a couple [on a flyer], that indicates ‘We do exist.’”). Additional suggestions included leveraging African American MSM in the popular media such as the Noah’s Arc television miniseries. Participants noted that positive experiences could be generated/facilitated by ensuring all intervention-related activities were “a safe place to be honest” and to “be welcoming no matter what [his sexual orientation and dis/comfort with non-heterosexual identity]..” Finally, participants were also uniformly enthusiastic about the appeal and potential promise of a couple-based intervention for African American, methamphetamine-involved male couples (e.g., “Couples [intervention] stimulates new thoughts and ways of seeing things…we are not alone with these problems, and it is real.”, “Participation shows others like ourselves that we really care about these issues and the community.”).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first report in the empirical literature regarding the adaptation of an evidence-based intervention originally designed for heterosexual couples to be revised specifically for male same-sex couples. Beyond the shift from heterosexuals to MSM, the study also focused on those residing at the nexus of several risk profiles—African Americans, methamphetamine users, and having longer-term intimate partners—the confluence of which presented additional challenges and considerations: (1) the dearth of existing research and attention paid to longer-term couple-dynamics among African American MSM and, to some extent, African American MSM and methamphetamine use; (2) a lead investigator who phenotypically does not match the target population; and (3) limitations on time, resources, and number/availability of topical experts. Service providers and researchers facing some or all of these challenges as they seek to adapt existing interventions for new target populations may benefit from the methods employed in this study: conducting multiple focus groups with the same participants; use of a theoretical framework that recognizes multiple, interacting domains of influence and accommodates different worldviews; and development/use of the Deconstruction/Reconstruction Matrix, a visualization tool that helps to ensure theoretical rigor, that intervention targets are maintained in the revision process, and tracking of the overall adaptation process.

High attendance rates during the series of focus groups, combined with the positive feedback, may signify that the adaptation process was an attractive and feasible endeavor for members of the target population. These conclusions are reinforced based on subsequent review/approval from: a panel of 8 service providers—who volunteered specifically for this study—from local community-based agencies serving African American MSM, methamphetamine users, and/or HIV-affected populations; a Program Review Panel consisting of 5 local community members who are charged with ensuring information/materials are understandable, accurate and appropriate; and a Community Advisory Board that provides input across a variety of HIV-related studies conducted at the research site.

A limitation of this work and the process include the intentional decision to rely on a small number of focus group participants, leading to ensuring caution about generalizability since the range of experiences and worldviews among the target population may not have been fully identified. Focusing on a narrow target population raises the concern about the generalizability and cost-effectiveness of this approach; it remains to be answered the extent to which these concerns are possibly countered by increased efficacy—presumably due to the highly tailored content—in conjunction with targeting a higher risk population. The anti-racist and anti-heterocentrist approach may also help temper these concerns about overspecification, yet may increase the requisite skill level of facilitators. Another limitation is the need to examine whether the adaptation process preserved the efficacy and/or effectiveness of the intervention. It is also noteworthy that when asking focus group participants to discuss concerns and issues of safety, they responded with information more related to notions of psychological and social “comfort.” Despite repeated attempts, little information appeared to be elicited regarding participants’ views on breaches of confidentiality (e.g., accidentally “outing” an individual) and other possible adverse events. The extent to which this latter issue reflects a shortcoming of the conduct of focus groups, a selection bias among the small sample of couples participating in the focus group (e.g., they were all comfortable identifying as gay), and/or is truly more generalizable to men/couples who meet the eligibility criteria remains unclear.

The aforementioned limitations inform the anticipated next steps. Specifically, the revised intervention will be pilot-tested with a small sample of African American, methamphetamine-involved male couples to obtain preliminary evidence and insight regarding efficacy as well as feasibility (e.g., recruitment, retention). The pilot test will also include protocols for facilitators to monitor process and record untapped areas or unanticipated information—including adverse events—in order to make any necessary further revisions to enhance generalizability, training of facilitators, and participant safety. The pilot test will also generate needed information on the means and venues for reaching, engaging, and recruiting the target population. Both the adaptation process and subsequent pilot testing represent crucial first steps in the trajectory of providing service providers with a couple-based HIV preventive intervention backed by the highest standards of scientific rigor for methamphetamine-involved, African American MSM.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) grant no. UR6PS000300. We thank Gordon Mansergh and Mahnaz Charania for their scientific guidance throughout the study. We also would like to acknowledge the contributions of Dale Frett and Jordan White, as well as the participants and couples who made this work possible. The content presented in this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of CDC, Harlem United, or the Columbia University School of Social Work.