All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

The Tale of Two Epidemics: HIV/AIDS in Ghana and Namibia

Abstract

Background:

In 2014, the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) introduced the 90-90-90 goals to eliminate the AIDS epidemic. Namibia was the first African country to meet these goals.

Objective:

To construct a comparative historical narrative of international and government responses to the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the two countries, to identify enabling and non-enabling factors key to mitigate the HIV/AIDS pandemic.

Methods:

We conducted a desk review of public documents, peer-reviewed articles, and media reports to evaluate actions taken by Namibia and Ghana’s governments, donors, and the public and compared disease prevalence and expenditure from all sources.

Results:

Namibia’s progress is due to several factors: the initial shocking escalation of infection rates, seen by donors as a priority; the generalizability of the epidemic generated, which resulted in overwhelming public support for HIV/AIDS programs; and a strong health system with substantial donor investment, allowing for aggressive and early ramp up of ART. Modest donor support relative to the magnitude of the epidemic, a weak health care system, and widespread household cost-sharing are among the factors that diminished support for universal access to HIV treatment in Ghana.

Conclusion:

Four factors played a key role in Namibia’s success: the nature of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, the government and international community's response to the epidemic, health system characteristics, and financing of HIV/AIDS services. Strengthening the health systems to support HIV/AIDS testing and care services, ensuring sustainable ART funding, empowering women, and investing in an efficient surveillance system to generate local data on HIV prevalence would assist in developing targeted programs and allocate resources to where they are needed most.

1. INTRODUCTION

The international community set several goals to coordinate the international response to the HIV/AIDS epidemic. These goals include the 3 by 5 initiatives launched by the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) and World Health Organization (WHO) in 2003 to treat three million people living with human immunodeficiency virus (PLHIV) in low- and middle-income countries by 2005 [1]; the 15 by 15 initiative of 2012 to treat 15 million PLHIV by 2015 [2], Getting to Zero initiative in 2012, which aspired for zero new HIV infections, zero AIDS-related deaths, and zero discrimination against PLHIV by 2015 [3]; and in 2014, the 90-90-90 goals, which aim to eliminate the AIDS epidemic by 2030 by having 90% of all PLHIV know their status, 90% of those with diagnosed HIV receiving sustained antiretroviral therapy (ART) (81% of PLHIV), and 90% of those on ART virally suppressed (73% of PLHIV) by 2020, with the goal of increasing these targets to 95% by 2030 [4]. These initiatives guide donors' responses to the HIV/AIDS epidemic. However, in recent years, donor funding to the HIV/AIDS epidemic has flattened or decreased, emphasizing the importance of using these scarce resources efficiently. Understanding what factors enable some countries to achieve goals set by the international community is essential to guide governments and donors' response to the HIV/AIDS epidemic and improve the use of HIV/AIDS international and domestic funding. Lessons from high-performance countries can inform and identify areas and programs where donors' support would be essential to improving testing, care, and treatment programs and eliminating new HIV infections.

In 2018, Namibia exceeded the UNAIDS 90-90-90 goal set for 2020, with 95% of PLHIV knew their status, 89% of PLHIV who knew their status were in ART, and 92% of those in ART had a suppressed viral upload. In comparison, only 58% of PLHIV knew their status in Ghana, 78% of PLHIV who knew their status were in ART, and 68% of those in ART had a suppressed viral upload. To understand why Namibia was able to exceed the 90-90-90 goals in 2018 in contrast to Ghana, we compared four indicators: (A) the nature of the epidemic, (B) the government and international community's response to the epidemic, (C) the capacity and actions of each country’s healthcare system, and (D) the level of financial support provided for the HIV/AIDS programs. This paper aims to construct a comparative historical narrative of international and government responses to the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Ghana and Namibia, to identify enabling and non-enabling factors key to mitigate the HIV/AIDS pandemic.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

We selected two countries in Africa, Ghana in eastern Africa and Namibia in southern Africa, to analyze the factors that led Namibia to be the first African country to achieve the 90-90-90 goal in 2018. We selected those two countries for the similarity in their initial response to the HIV/AIDS epidemic: (A) the first AIDS case for both countries was reported in 1986, (B) both depended on sentinel surveillance systems to monitor the epidemic, and (C) both used a multi-sectoral approach to fight the epidemic. However, Ghana and Namibia are different in other ways of interest: (A) The economic status of those countries are different: Ghana is a middle-income country, while Namibia is an upper-middle-income country, (B) Ghana has a low prevalence of HIV/AIDS, ranking 33rd globally, while Namibia has a high HIV/AIDS prevalence, ranking 5th in the world, (C) Ghana has low HIV/AIDS treatment coverage, while Namibia has high ART coverage, and (D) While Namibia has a strong public health system, Ghana is one of the 49 counties classified by the WHO as being in a critical shortage of health workforce [5, 6].

We conducted a desk review of public documents, reviewed each country's HIV/AIDS reports, national HIV/AIDS strategies and frameworks, published peer-reviewed articles, reports by funding agencies and media reports, and conducted interviews with four graduate students from Ghana and Namibia studying at the Heller School for Social Policy and Management, Brandeis University who had prior experience in HIV/AIDS programs in their countries, to better understand the actions taken by Namibia and Ghana’s governments, donors, and the public. We analyzed the prevalence and incidence of HIV/AIDS among the general population and the population at high risk of HIV/AIDS and AIDS-associated mortality using data from UNAIDS. We reviewed literature covering the healthcare system in both countries to analyze the health system capacity to deal with the HIV/AIDS epidemic. We reviewed HIV funding from US and non-US sources as reported at the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Credit Reporting System (CRS) database and PEPFAR Funding Data Sources to understand the source of funding and allocation of HIV/AIDS funding across HIV/AIDS activities. In addition, we captured HIV/AIDS spending by sources and programs using UNAIDS data.

3. RESULTS

3.1. The Nature of the Epidemic

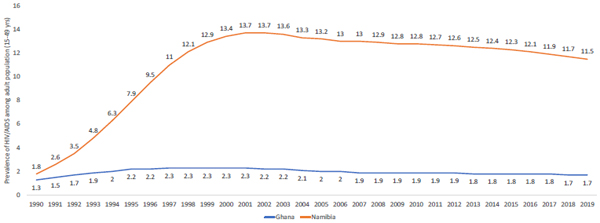

Fig. (1) illustrates the trend in HIV/AIDS prevalence among adults 15 to 49 years of age in Namibia and Ghana. In early 1990 the prevalence among adults 15-49 in Namibia was 1.8. Due to the increase in trade in the post-apartheid economy, HIV, a new disease to Southern Africa at that time, spread throughout the 1990s, with prevalence rising to 13% by 2000. In 1996, HIV/AIDS became the leading cause of death in Namibia [7], and life expectancy fell from 61 years in 1993 to 50 years in 2003 [8]. However, new HIV infections have halved since 2004, and life expectancy increased by 8 years from 56 in 2005 to 64 in 2016 [9]. The incidence rate started to drop among adults in the late 1990s, and the country saw a decline in the prevalence of HIV/AIDS by mid-2000.

Namibia has a generalized mature epidemic transmitted mainly through heterosexual activities and Mother To Child Transmission (MTCT) [10]. Key populations are at higher risk of being infected. Between 2016 and 2019, HIV/AIDS prevalence was 13.3% among adults 15-49, 24% among men who have sex with men (MSM), and 20% among Female Sex Workers (FSW). Women bear a disproportionate burden of the HIV epidemic. For adults over the age of 25, 17.8% of women were living with HIV compared to 13.5% of men [9]. The population density was positively correlated with HIV/AIDS cases. The prevalence of HIV was highest in the Khomas region, centered around Namibia’s capital, and six northern regions, as well as urban hot spots in coastal towns and along main roads connecting northern and southern Namibia [9].

In Ghana, the first reported AIDS case was for a FSW who worked in a neighboring country. During the early years of the epidemic, 80% of all AIDS cases were imported from neighboring countries. The HIV prevalence among adults 15 to 49 years of age increased from 1.3% in 1990 to 2.3% in 1997 but declined in 2002 to 2.2% and has remained fairly flat since then. The incidence rate per 1,000 adults 15 to 49 years of age was highest in early 1990 and has steadily declined since 1994. While new HIV infections (incidence) are decreasing in Namibia, Ghana is one of 35 countries accounting for 90% of new HIV infections globally [11].

The AIDS mortality rate per 1,000 adults 15-49 years of age lagged behind the number of new cases and peaked in 2004 but fell after that. Ghana has a mixed epidemic where HIV transmission occurred in the general population (average 1.7% with regional variation in 2017) as well as key populations such as FSW (6.9% in 2015), MSM (18.1% in 2017), people who inject drugs, and prisoners (2.5%) [12]. In 2014, the prevalence of HIV/AIDS among women 15-49 years of age was twice as high as that of men. According to the 2015 HIV Sentinel Survey, a cross-sectional survey targeting women attending antenatal clinics in selected ANC sites [13], HIV cases were reported in all the 10 regions of Ghana. However, the majority of these cases were clustered in Western, Ashanti, Greater Accra, and Eastern Regions.

As illustrated in Fig. (1), the Namibia epidemic spread rapidly through 2003, but since then, the prevalence rate has been decreasing. Ghana, on the other hand, a country with about 12 times more people, had an epidemic that was far less rampant but no evidence of declines in prevalence.

Table 1 compares the key HIV/AIDS indicators between Ghana and Namibia in 2019 as reported by UNAID [14]. By 2019, many indicators of epidemic control looked far better in Namibia in contrast to the huge initial crush of the epidemic there. ART coverage and viral load suppression indicators are much higher in Namibia. Consequently, HIV mortality rates among PLHIV are lower,1% vs 4% for Ghana. In 2019, Namibia's ART coverage exceeded Ghana's not only for the general population but also for HIV-positive pregnant women. As a result, the MTCT was 19% in Ghana compared to only 4% in Namibia. In addition, awareness of HIV status, in general, is higher in Namibia compared to Ghana (95% vs 58%).

| Key HIV/AIDS Indicator | Ghana | Namibia |

|---|---|---|

| Population in 2019 | 30,417,856 | 2,556,403 |

| New HIV infections in 2019 | 20,000 | 6,900 |

| New HIV infection- Children (0-14) | 3,000 | 410 |

| New HIV infection-Adolescents (10-19) | 2,100 | 730 |

| New HIV infection-Young people (15-24) | 5,600 | 2,000 |

| New HIV infection-Adults (15+) | 17,000 | 6,400 |

| New HIV infection-Adults (15-49) | 16,000 | 5,900 |

| New HIV infection-Adults (50+) | 1,300 | 550 |

| HIV incidence: prevalence ratio in 2019 | 5.86 | 3.10 |

| HIV prevalence in 2019 for young people (15-24) | 0.70 | 3.80 |

| HIV prevalence in 2019 for adults (15-49) | 1.70 | 11.50 |

| HIV prevalence in 2019 for adults (15+) | 1.70 | 12.70 |

| Persons living with HIV in 2019 | 340,000 | 210,000 |

| PLHIV-Children (0-14) | 26,000 | 10,000 |

| PLHIV-Adolescents (10-19) | 20,000 | 12,000 |

| PLHIV-Young people (15-24) | 38,000 | 18,000 |

| PLHIV-Adults (15+) | 320,000 | 200,000 |

| PLHIV-Adults (15-49) | 260,000 | 150,000 |

| PLHIV-Adults (50+) | 60,000 | 51,000 |

| People living with HIV who know their status (%) | 58% | 95% |

| Persons in ART, 2019 | 153,901 | 177,174 |

| % of persons in ART | 45% | 85% |

| Number of people living with HIV who have suppressed viral loads | 105,400 | 163,800 |

| % virally suppressed: People living with HIV who have suppressed viral loads | 31% | 78% |

| AIDS-related mortality in 2019 | 14,000 | 3,000 |

| AIDS-related mortality rate among PLHIV | 4% | 1% |

| Mother-to-child transmission | - | - |

| Coverage of pregnant women who receive ART for PMTCT | 75% | 100% |

| Mother-to-child transmission rate | 19% | 4% |

| Early infant diagnosis | 65% | 99% |

3.2. Government's Response

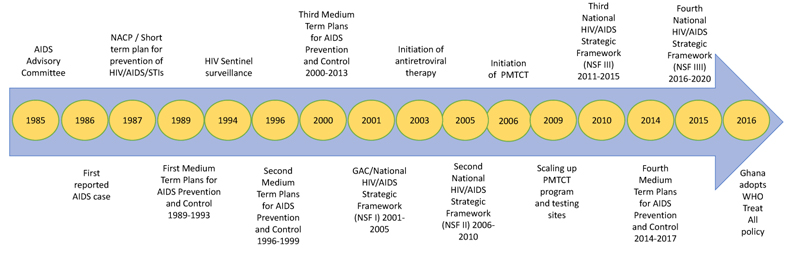

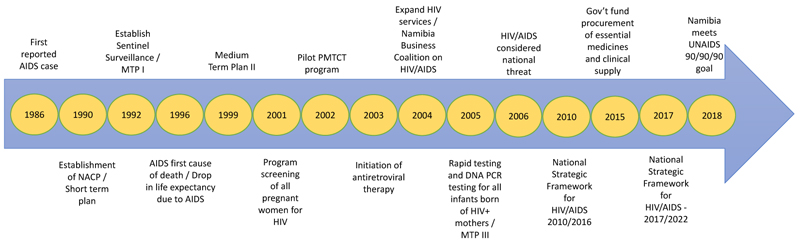

At the inception of the epidemic, Ghana and Namibia both utilized “media campaigns” to increase awareness of the disease and how to prevent the spread of the virus. The awareness campaigns promoted safe sex messages using print and electronic media that focused on abstinence, mutual faithfulness to one partner, and the use of condoms. The program utilized tools such as social marketing, peer education, and school-based programs in addition to workplace activities to increase awareness of the disease and promote a healthy lifestyle to mitigate the spread of HIV/AIDS. To monitor the HIV/AIDS epidemic, Namibia established the HIV sentinel surveillance system in 1992, and Ghana established a similar system in 1994. The two countries developed short- and mid-term plans as well as national HIV strategies and frameworks to combat the disease using a multi-sectoral approach and initiated several HIV/AIDS programs, including blood safety program, prevention of MTCT (PMTCT) program, and the ART program, as presented in Figs. (2 and 3). While the scope of Ghana’s and Namibia’s programs was similar, the scale was very different. While Ghana suffered from chronic underfunding for its HIV/AIDS program and lack of trained clinicians and essential staff, Namibia’s expansion of these programs was possible due to the capacity of its health system, technical support from donors, and substantial funding for these programs.

Note: 2002 Ghana received funding from the Global Fund; 2007 Ghana received PEPFAR funding; 2014 UNAIDS sets 90-90-90 goal. NACP denotes National AIDS Control Program. GAC denotes Ghana AIDS Commission.

Note: 2004 Namibia received PEPFAR funding; 2005 Namibia received funding from the Global Fund; 2014 UNAIDS set the 90-90-90 goal. NACP denotes National AIDS Control Program.

3.3. Healthcare System Capacity

Namibia's well developed public health care system focuses on primary health care with horizontal integration of public health and curative care services. There are strong linkages between community health workers, health centers, and district hospitals [15]. HIV services are integrated into the primary health care system, providing comprehensive, integrated, and patient-centered care. Namibia does not have a national public insurance system. Health services for the majority of the population are provided at public health care facilities funded mainly by the government with some resources from donors. Services at government facilities are heavily subsidized by the government with affordable and flat user fees that vary by facility type [16]. The private health insurance in Namibia covers 18% of the population and includes HIV/AIDS care in its benefits package [17].

In Ghana, health care is provided mainly by the public sector through a five-tiered system consisting of health posts, health centers and clinics, district hospitals, regional hospitals, and tertiary hospitals [17, 18]. Administratively, Ghana has ten regions divided into 275 districts [11]. Districts are divided into sub-districts, which are further sub-divided into Community Health Planning and Services zones. At the regional level, curative services are provided at the regional hospital. At the district level, curative care services are provided by the district hospitals, many of which are mission-based. At the subdistrict level, both preventive and curative services are provided by health centers and through outreach services to communities within the health centers' catchment areas [17]. Ghana’s public health insurance system, The National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) [11] improved access to healthcare services for 45% of the population. While NHIS covers HIV/AIDS symptomatic treatment for opportunistic infections, HIV ART medication is explicitly excluded from its benefits [19]. However, ART is heavily subsidized by the National AIDS Program and provided free of charge at public facilities when available [20]. Ghana’s health care system remains dependent on international financial and technical assistance.

The healthcare system's capacity and personnel and financial resources allocated to the HIV/AIDS response are vastly different in those countries. For example, Ghana’s weak HIV/AIDS commodity security system experienced frequent stock-out of HIV tests, in addition to the chronic shortage of testing kits (to ensure safe blood transfusion), scarcity of HIV counseling and testing facilities, limited coverage of ART services, and lack of HIV/AIDS-primary care integration [21]. In contrast, Namibia built its medical staff capacity for blood screening and efficient HIV testing and diagnosis, integrated and expanded PMTCT services (by 2015, all infants born of HIV+ mothers were screened for HIV within 2 months of birth), built capacity in HIV counseling services, and made HIV counseling and testing facilities available and accessible. While both Ghana and Namibia introduced the ART program in 2003, by 2016, only 145 districts out of 275 had ART sites in Ghana, and the unmet need for ART remained high (approximately 65% of PLHIV) with low pediatric ART coverage (less than 30%). By contrast, with significant support and contribution from donors, Namibia covered ART in all hospitals and some clinics. To implement the ART program's uptake, Namibia, with the technical support of donors, established national guidelines, rollout plans, health information systems, and building capacity to deliver ART services. The rollout of ART in Namibia had a positive impact on health providers' attitudes toward PLHIV [22].

3.4. Financing of HIV/AIDS Services

Namibia is one of the core PEPFAR countries that received funding in 2004 and is a recipient of Global Fund grants since 2005. Donors played a significant role in enabling Namibia to rollout several important HIV/AIDS programs, most notably, the ART program. In 2017, Namibia spent $447.28 per capita on health care, of which $113 was spent on HIV/AIDS [23]. The total expenditure on HIV/AIDS activities in 2017 was $283 million or $1,347 per prevalence case. Forty-four percent of all HIV/AIDS spending was from public sources, 26% from private sources, and 29% from donors. Out-of-pocket represents a small portion (2%) of HIV/AIDS spending, as presented in Table 2. Between 2015 and 2019, PEPFAR contributed $252 million for HIV/AIDS activities; 29% of that contribution was spent on care and treatment, 16% on prevention, and 8% on testing, as presented in Table 3. As noted in Table 2, in recent years, public spending on HIV/AIDS in Namibia increased.

| - | Ghana | Namibia |

|---|---|---|

| Year of HIV/spending reported by UNAIDS | 2016 | 2017 |

| Total spending on HIV/AIDS from all sources | $68,079,469 | $282,827,940 |

| Per capita spending on HIV/AIDS activities | $2.24 | $113.38 |

| Per prevalence case spending on HIV/AIDS activities | $200.23 | $1,346.80 |

| Source of funding | - | - |

| % of total public | 10% | 44% |

| % of total private | 28% | 26% |

| % of households | 28% | 2% |

| % of international | 63% | 29% |

| % of PEPFAR | 11% | 22% |

| Spending by program | - | - |

| % treatment, care and support (TCS) all sources | 73% | 75% |

| % of TCS spending funded by PEPFAR | 0.4% | 22% |

| % HIV/AIDS spending on prevention from all sources | 9% | 6% |

| % of prevention spending funded by PEPFAR | 59% | 66% |

| % HIV/AIDS spending on social programs from all sources | 18% | 17% |

| % of social program spending funded by PEPFAR | 32% | 2% |

| - | Ghana | Namibia |

|---|---|---|

| Total PEPFAR expenditures (2015-2019) | $44,912,121 | $251,711,605 |

| PEPFAR spending per capita | $1.48 | $100.91 |

| PEPFAR spending per PLHIV | $132 | $1,199 |

| % on care and treatment | 19% | 29% |

| % on testing | 6% | 8% |

| % on prevention | 9% | 16% |

| % on socioeconomics | 1% | 4% |

| % on above-site Programs | 31% | 18% |

| % on program management | 33% | 25% |

Ghana was the first country to receive a Global Fund grant. In 2007, PEPFAR began its operation in Ghana [24]. In 2016, Ghana spent $67.71 per capita on healthcare, of which $2.24 was spent on HIV/AIDS [25]. In 2016, the total expenditure on HIV/AIDS activities was $68 million or $200.23 per prevalence case. Only 10% of all HIV/AIDS spending was from public sources. Households contribute 28% to all HIV/AIDS spending and donors contribute 63% of total HIV/AIDS spending, as presented in Table 2. Between 2015 and 2019, PEPFAR contributed $45 million to HIV/AIDS activities. Most of PEPFAR's contribution to Ghana was channeled toward technical assistance [12], while 19% was spent on care and treatment, 9% on prevention, and 8% on testing, (Table 3).

The expenditures per capita and per PLHIV were vastly more in Namibia; per capita was $2.24 in Ghana compared to $113.38 in Namibia, and the expenditure per PLHIV was $145.80 in Ghana compared to $200.23 in Namibia. The donor contributions to the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Namibia are considerable. Yet, Namibia is less dependent on donors and on households for funding the response compared to Ghana, where international donors contribute 63% of all HIV funding (contrasted with 29% in Namibia). Most critically, households in Ghana were funding about the same fraction of HIV spending as were the donors (28%), while in Namibia, households funded only 2% of the total HIV burden.

While the prevalence of HIV/AIDS in Namibia was much higher than in Ghana, the crude number of HIV/AIDS cases in Ghana was much higher. Moreover, the expenditure per prevalence case in Ghana was 15% of what Namibia spent. The difference in donors’ contributions, including those from PEPFAR, to the HIV/AIDS epidemic between Ghana and Namibia is substantial: PEPFAR contributed $1.48 per capita, or $132 per prevalence case in Ghana compared to $100.91 per capita, or $1,199 per prevalence case in Namibia. Fig. (4) illustrates donors' contributions to HIV/AIDS between 2002 and 2018.

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Ghana’s Situation in Meeting UNAIDS Goals

Ghana took steps to mitigate the impact of the HIV/AIDS epidemic before the first reported AIDS case in 1986. The government was committed to fighting the disease and adopted interventions to control it, such as HIV/AIDS awareness campaigns in schools and changing laws and regulations to protect the population at higher risk of becoming infected. However, the low HIV/AIDS prevalence in Ghana and the mixed epidemic, with higher prevalence among key populations, did not mobilize the needed support to set HIV/AIDS epidemic as a priority at domestic or donor levels. Donors’ contribution to Ghana's HIV/AIDS response was mainly for technical assistance [12]. Furthermore, the lack of resources, a weak health system, and reluctant donors' financial commitment limited the government's ability to respond effectively to the HIV/AIDS epidemic, with dire consequences for PLHIV.

In 2016, The Global Fund adopted a system strengthening approach to fighting HIV/AIDS in epidemic countries [27]. This approach was critical for Ghana to meet the country's commitment to the UNAIDS 90-90-90 goals. Ghana's adaptation of these goals resulted in a significant change in policy, HIV/AIDS programming, and budgeting [28]. The National Strategy Plan (NSP) for 2016-2020 aimed to achieve the first and second goals and focused on system strengthening to meet the third goal [28]. However, several factors limited Ghana's ability to meet those goals. Health system obstacles, including stock-outs of test kits, lack of qualified health care workforce, discriminatory practices against key populations [11], and a weak testing strategy for the general population, contributed to the low HIV testing. Modest efforts improved HIV testing rate among adults, where 13% of women and 6% of men tested for HIV and received their results [29]. However, the high HIV testing for women is due to HIV services provided at antenatal clinics, which are attended by 90% of pregnant women [29]. In 2018, the Global Fund found that only 37% of PLHIV started treatment, but 22% would subsequently be lost to treatment due to lack of a tracking system and stock-outs for an average of 54 days for key medications. At the national level, only 33% of PLHIV received a viral test, and the viral load suppression was at 64%, risking high mortality and undetected drug resistance [11]. Investment in healthcare infrastructure and human resources, and an efficient surveillance system are needed to control and eliminate HIV/AIDS in Ghana. These investments require sustainable HIV/AIDS funding from both international and domestic sources [30].

Financing HIV/AIDS activities is a crucial obstacle facing Ghana. To achieve the second UNAIDS goal, Ghana needed $80 million in 2015 for treatment alone, but less than 24% ($19 million) was budgeted for treatment in that year [31, 32]. To close the finance gap, Ghana mobilized domestic resources for HIV/AIDS treatment by establishing the AIDS Trust Fund in 2015. However, the resources collected through the Fund were not sufficient to meet the funding gap. As a result, Ghana initiated targeted programs that focused on PMTCT and early infant diagnosis as a way to improve diagnosis and coverage of ART and targeted key populations in the three regions with the highest concentration of PLHIV [28]. HIV/AIDS services were not expanded to other parts of the country. Without the geographic penetration of testing, care, and treatment services, increasing ART coverage has been a challenge, especially among hard-to-reach populations [30]. While the UNAIDS goals aim to improve HIV/AIDS outcomes, standardized goals might have an adverse impact when donors use these goals to measure a country's performance [28]. The current HIV strategy in Ghana focuses on shifting the HIV/AIDS control program from a generalized population-based model to a high HIV-burden geographical and key population focus, reducing new infections in key populations and increasing retention in care and adherence to treatment [29]. However, challenges persist due to a lack of data and resources to incorporate target populations in decision making and advocating on their own behalf, and to improving the quality of services provided to the key populations [12].

4.2. Namibia’s Situation in Meeting USAID Goals

In Namibia, the high prevalence of HIV/AIDS and the generalization of the epidemic were key to mobilizing domestic and international support to the HIV/AIDS response [33]. The rapid increase in the use of ART since 2004 transformed HIV/AIDS from an invariably fatal illness to one that is successfully managed [34]. Donor funding (mainly through PEPFAR and the Global Fund) [35], was instrumental in the initiation, roll out, and expansion of both the ART and PMTCT programs. The government’s commitment to fight HIV/AIDS translated into support for the ART program [36]. In 2014, The government of Namibia paid for 64% of HIV/AIDS programs and purchased most of the ART medication. Of the $200 million Namibia spent on HIV/AIDS, only $71 million came from PEPFAR and $10 million from the Global Fund.

Source: Computed from KFF Analysis of HIV funding from non-US donors as reported to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Credit Reporting System (CRS) database and KFF Analysis of PEPFAR Funding Data Sources. In 2019, the population in Namibia was estimated at 2,556,403, and 30,417,856 in Ghana [14].

Namibia's strong health system helped in scaling up the testing, care, and treatment program and identifying new HIV infections. Namibia has a good trace and test program known as Index Partner Testing, which aims to trace and test sexual partners of individuals newly diagnosed with HIV. For the newly diagnosed, Namibia’s trio system connected newly diagnosed individuals with a support group of two friends or family members to keep this person on ART for the first six months. The individual then joined a larger support group of people undergoing ART treatment. Currently, Namibia is offering pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for the key high-risk populations [36].

4.3. Lessons Learned

Several lessons can be learned from the trajectory and outcome of HIV epidemics in Ghana and Namibia. First, gaining support for countries’ HIV/AIDS program is important. The difference in countries’ progress in reaching UNAIDS 90-90-90 goals by 2018 could be owed to the shocking escalation of infection rates in the early days in Namibia (and seen by donors as a priority emergency problem) and the overwhelming public support for saving lives among PLHIV. Second, the magnitude and generalizability of the pandemic in Namibia allowed the government and international donors to justify the substantial investment in HIV/AIDS prevention and treatment programs. In contrast, Ghana’s HIV/AIDS policy focused on key populations, masking the risk of infection among the general population. These policies may have been efficient, but they may have also jeopardized the general support and finance of HIV/AIDS prevention and treatment programs. Though Ghana is a much poorer country than Namibia, the government and international donors provided less financial support and left households in Ghana financially responsible for funding HIV services.

Third, the initial international funding enabled aggressive and early ramp up of ART in Namibia. When taken as prescribed, ART lowers viral load, which allowed Namibia to successfully use ART treatment as prevention (TasP), curtailing further transmission and improving outcomes for PLHIV [26]. Accessibility to ART not only saved countless lives in Namibia, but it enabled a focus on getting those who were aware of their HIV status both into treatment and sustained in treatment--and facilitated the ability to meet the UNAIDS Goals. In contrast, Ghana’s less thorough ART treatment sites rollout across the country may explain, in part, the differences in uptake of treatment services between Ghana and Namibia.

Fourth: A strong health care system and easy access to HIV/AIDS prevention and treatment allowed the government of Namibia to reduce new infections, increase retention in care and adherence to treatment. In contrast, access to treatment was expensive and not a priority in Ghana. Ghana’s challenged health system and widespread household cost sharing might have led to weak support for universal access to HIV treatment and drugs.

CONCLUSION

The nature of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, health system capacity, funding and donor support were essential for Namibia to achieve impressive progress toward achieving the UNAIDS 90-90-90 goals in 2019 [14]. This accessibility not only saved countless lives, but it enabled a focus on getting those infected persons who were aware of their HIV status into treatment and sustained in treatment--and facilitated the ability to meet the UNAIDS goals. The difference in countries’ progress in reaching UNAIDS 90-90-90 goals by 2018 can be owed to the shocking escalation in infection rates in the early days in Namibia (and seen by donors as a priority emergency problem) and the overwhelming public support for saving lives among PLHIV. Access to treatment was not such a priority in Ghana, and their weak health system and widespread household cost-sharing are among the factors that led to not being able to support universal access to HIV treatment and drugs.

While global spending on HIV in sub-Saharan Africa peaked in 2013 [37], it has since declined, jeopardizing existing efforts to combat HIV. Renewed commitment to support ART programs is essential to getting the world on track to bring HIV infection under control. Strengthening health systems to support HIV/AIDS testing and care services, ensuring sustainable ART funding, empowering women, and investing in an efficient surveillance system to generate local data on HIV prevalence will assist in developing targeted programs and allocate resources to where they are needed most [38]. Namibia showed that access to ART decreased systematic discrimination against PLHIV. A key lesson we have learned from Namibia is that care and treatment for PLHIV save lives and prevent new infections. However, HIV/AIDS care and treatment provision require investment in health care infrastructure and human resources, addressing the social and cultural obstacles facing vulnerable and key populations, especially young women. The COVID-19 pandemic emphasized the vulnerability of health care systems, especially the delivery of health services to PLHIV. A report by the Global Fund suggested HIV/AIDS services fell by more than 37% in 2020 due to the pandemic [39, 40]. The disruption of critical HIV services, especially testing, diagnosis and treatment services, and its potential impact on a new surge in infections calls for urgent efforts to progressively resume and increase investment in HIV/AIDS programs to regain the lost progress made to control HIV/AIDS in epidemic countries due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| ART | Antiretroviral Therapy |

| CRS | Credit Reporting System |

| FSW | Female Sex Worker |

| HIV/AIDS | Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection / Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome |

| MSM | Men who have sex with men |

| MTCT | Mother-to-Child Transmission |

| NHIS | The National Health Insurance Scheme |

| NSP | National Strategy Plan |

| OECD | Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| PEPFAR | President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief |

| PLHIV | People Living with HIV |

| PrEP | Pre-exposure Prophylaxis |

| TasP | Treatment as Prevention |

| TCS | Treatment Care, and Support |

| UNAIDS | Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTION

Yara A. Halasa-Rappel, Gary Gaumer and A.K. Nandakumer worked on the methodology, collected and analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript, Deepa Khatri worked on data collection and data analysis, Monica Jordan and Clare Hurley worked on writing and editing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTI-CIPATE

Not applicable.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

Not applicable.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

FUNDING

This paper was produced with funding from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Division of Global HIV/AIDS & TB (DGHT) under Cooperative Agreement Number U2GGH001531. Its contents are solely the responsibility of Cardno and Brandeis University and do not necessarily represent the official views of the CDC.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Bertha Akua Asare, Prince Kwarase, Dorcas Osei, and Ekwu B.B.Ochibgo for their input on the role governments in each country played in deploying projects and launching campaigns to control the HIV epidemic. The authors also thank Jennifer Katz and her team at the Kaiser Family Foundation for providing the donors’ financial contribution to the HIV epidemic in Ghana and Namibia.