SYSTEMATIC REVIEW

Barriers and Facilitators to HIV/AIDS Testing among Latin Immigrant Men who have Sex with Men (MSM): A Systematic Review of the Literature

Aiala Xavier Felipe da Cruz1, Roberta Berté2, Aranucha de Brito Lima Oliveira2, Layze Braz de Oliveira3, João Cruz Neto4, Agostinho Antônio Cruz Araújo3, Anderson Reis de Sousa5, Isabel Amélia Costa Mendes3, Inês Fronteira6, Álvaro Francisco Lopes de Sousa7, *

Article Information

Identifiers and Pagination:

Year: 2023Volume: 17

E-location ID: e187461362307030

Publisher ID: e187461362307030

DOI: 10.2174/18746136-v17-230720-2023-12

Article History:

Received Date: 06/04/2023Revision Received Date: 09/06/2023

Acceptance Date: 14/06/2023

Electronic publication date: 07/08/2023

Collection year: 2023

open-access license: This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Public License (CC-BY 4.0), a copy of which is available at: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode. This license permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Objective:

This study aims to identify barriers and facilitators of HIV/AIDS testing among Latin American immigrant men who have sex with men (MSM).

Methods:

A systematic literature review was conducted using the following databases: MEDLINE via the US National Library of Medicine's PubMed portal; Web of Science (WoS); Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL); Scopus; and Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature (LILACS).

Results:

Twelve studies were eligible. Overall, the studies indicated that Latin American immigrant MSM have low HIV testing rates. This low testing rate can be influenced by various factors, including knowledge and awareness about HIV; stigma, discrimination, and confidence in health services; barriers to accessing healthcare; type of partnerships and relationships; lack of knowledge about their rights; migration and documentation status; and personal, cultural, and religious beliefs

Conclusion:

Public health interventions aimed at increasing HIV testing among Latin immigrants should directly address the fundamental reasons for not getting tested. This approach is likely to be more successful by taking into account the specific needs and circumstances of Latin immigrant men who have sex with men.

1. BACKGROUND

Despite advances in scientific knowledge, treatment, prevention, and awareness, HIV remains a robust public health problem and a challenge to the global scene. The main form of HIV/aids transmission occurs through unprotected sexual relations, whether through anal, vaginal, or oral cavities, making it a sexually transmitted infection. The epidemic has taken on new characteristics over the decades, requiring control strategies and effective prevention actions [1].

In 2022, around 43.8 million people suffered from HIV, and 680,000 died as a result of aids-related complications [2]. Although the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/aids aims to end the epidemic by 2030, however, there are many barriers and challenges to this pathology, especially when considering the COVID-19 pandemic and post-pandemic period. People living with HIV were more susceptible to contracting the virus, increasing the risk of death and the severity of the disease [3].

The vulnerability of the LGBT+ population and infectious diseases such as HIV/aids is reported worldwide, driven by stigmas related to sexual behaviors/orientations with a higher risk of infection. This prejudice especially targets gays, bisexuals, and men who have sex with men (MSM) [4, 5].

It is important to note that the MSM population is directly related to vulnerabilities associated with HIV infection [6]. Therefore, it is discriminatory to inhibit testing, whether through stigma or discrimination, given the high rate of infection in this group. Testing in this population is crucial for prevention and early detection of HIV.

The test is offered publicly in almost all regions of the world. It is known that the care related to the testing process requires a prepared and receptive team for the patient, however, the lack of trained professionals, acceptance of sexuality or sexual condition, fear of the result, and a lack of information are prominent barriers for MSM (men who have sex with men) groups who frequent services, many of whom do not undergo testing due to fear, which prevents early diagnosis and accelerates negative impacts if infected [7, 8].

It is valid to understand that many MSM do not believe they are at risk and therefore do not undergo regular testing [9]. Therefore, strategies for monitoring, active searching, distribution and disclosure of tests, safety in the procedure, preservation of confidentiality, overcoming fears, and normalizing testing by users are necessary for changes in this thinking [10].

In MSM populations, the breakdown of social networks, increased risky sexual behavior, increased exposure, communication barriers, limited access to care, and high stigma contribute to HIV infection cases [11]. However, an important weakness is the observance of testing in Latin American MSM, requiring testing measures for this population as well.

Guidelines emphasizing the importance of advocating for HIV testing as a fundamental aspect of ensuring widespread access to treatment and care have been issued by numerous global organizations. Existing literature indicates that the main obstacles to accessing HIV testing services among migrant populations are related to administrative access, legal factors, language difficulties, and cultural barriers. However, limited research has been conducted on the barriers and facilitators of HIV/AIDS testing specifically among Latino immigrant MSM, considering their double vulnerability as both immigrants and MSM. Therefore, this review is justified by the scarcity of existing literature on the topic and the need to understand the barriers and facilitators that influence HIV testing among the Latino MSM population. Addressing these knowledge gaps directly impacts the promotion of sexual and reproductive health for this marginalized population. Accordingly, the objective of this study is to identify the barriers and facilitators of HIV/AIDS testing among Latino immigrant MSM.

2. METHODS

This is a systematic literature review conducted in accordance with the guidelines provided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 [12]. The protocol for this review has been registered on the Open Science Framework platform (DOI: 10.17605/OSF.IO/6GFV8).

In order to develop the guiding question, the PECO strategy [13] was utilized, which uses an acronym to represent the following components: “Population” (MSM immigrants), “Exposure” (HIV/AIDS), “Comparison” (not previously studied), and “Outcome” (Testing). The PECO strategy includes additional factors, specifically related to the types of studies adopted, which aids in managing the content and variables of intervention and exposure more effectively during literature searches. For this particular study, the focus was on the exposure component rather than the intervention, considering the formulation of clinically directed questions.

As a result, the guiding question for this systematic review was formulated as follows: “What are the barriers and facilitators to HIV/AIDS testing among Latino immigrant MSM?”

The inclusion criteria encompassed original studies in any language, without a temporal restriction, and utilizing various methodological designs. The included studies addressed HIV testing among the MSM population and explored the primary barriers and facilitators to improving testing rates. Studies that solely focused on STIs without specifying HIV and those involving groups other than MSM were excluded.

Between June and August 2021, a literature search was conducted, with an additional search carried out from November to December 2022 to identify any studies published subsequent to the initial search. The search strategies employed were applied to various databases, including Scopus (Elsevier) - last searched August 2021; LILACS; MEDLINE (NCBI) - last searched August 2021, Web of Science (WoS) last searched August 2021 and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) - last searched August 2021.

The following combination of keywords was used: (HIV* OR Aids*) AND Test* AND Immigrants OR migrants, respecting the specificities of the databases and search engines, as follows:

2.1. MEDLINE and Web of Science

(MeSH descriptors): HIV OR “Human immunodeficiency virus” OR AIDS OR “Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome” OR “HIV infections” AND Immigrant OR Migrant OR Refugee OR Emigrant OR “Displaced people” OR Foreigner OR “Foreign-born” OR “Non-national” AND Test OR Tests OR Tested OR Testing.

2.2. Scopus

HIV OR “Human immunodeficiency virus” OR AIDS AND Immigrant OR Migrant OR Refugee OR Emigrant AND Test OR Tests OR Tested OR Testing.

2.3. CINAHL

HIV OR “Human immunodeficiency virus” OR AIDS AND Immigrant OR Migrant OR Refugee OR Emigrant OR “Foreign-born” AND Test OR Tests OR Tested OR Testing.

2.4. LILACS

HIV OR AIDS AND Immigrant OR Migrant AND Test OR Tests OR Tested OR Testing.

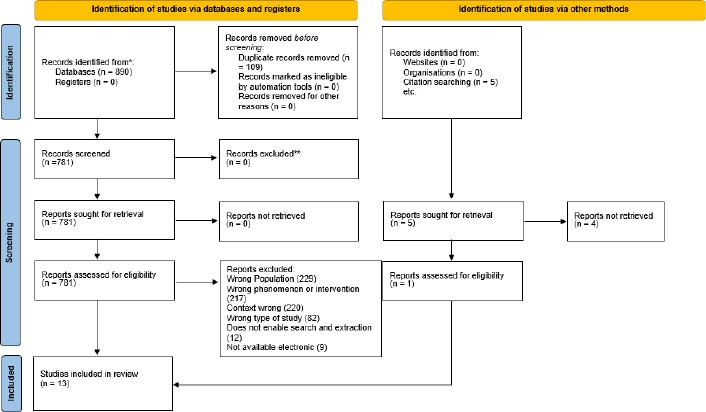

The located studies were exported to the Rayyan ® software to identify and exclude duplicates. Subsequently, two independent reviewers analyzed the studies, considering the following order: (1) reading titles; (2) reading abstracts of the selected studies from the previous step; (3) full-text reading and text selection. As it was a masked stage, there were disagreements regarding some studies, which were sent for analysis by a third reviewer (Fig. 1).

All selected studies included in this research were exported to a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet for data extraction, including the title, objective, methods, results, year and place of publication, and research design. It should be noted that there were potential studies that did not meet the predefined inclusion criteria and were consequently excluded from the sample [9-11]. This research received no financial support, and there are no conflicts of interest among the authors.

Finally, a qualitative and critical analysis of the article was performed, and the results were discussed and presented. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze the data and describe the overall view of the publications.

3. RESULTS

In relation to the characteristics of the articles identified and included in this review, a majority of them were published in the United States (n = 12). This reflects the migratory patterns within the country and highlights the substantial presence of Latino immigrant MSM in the American territory. In terms of publication year, 2013 was the most prevalent, with 3 articles published. Table 1 presents a comprehensive overview of the selected studies in this review, arranged according to their title, objectives, methods, results, and main findings.

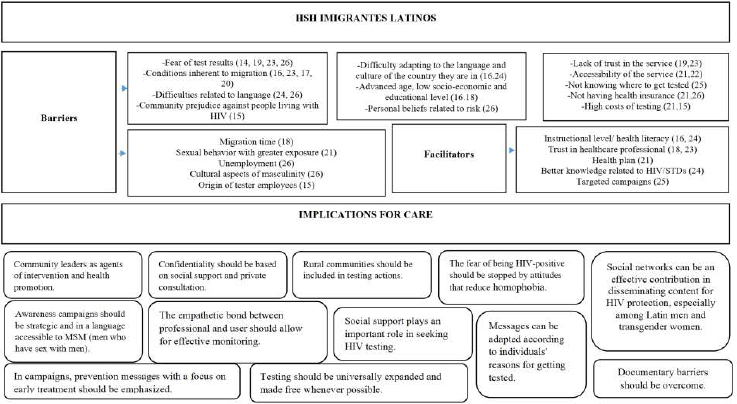

Next, the main findings are grouped in Fig. (2).

|

Fig. (1). Flowchart showing the sampling of the systematic review according to the PRISMA group, 2023. |

|

Fig. (2). Barriers and facilitators for HIV testing among immigrant latin MSM. |

| Authors/Refs. | Objectives | Methods | Results | Key-issue |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rhodes et al., 2020 [14] |

Test a peer-to-peer/social network intervention in Spanish aimed at increasing HIV testing among gay, bisexual, and other MSM Latin immigrant networks | This is a randomized study, conducted on 21 social networks of Latinx MSM, aged 18-55 years. Individual interviews were conducted to document experiences, needs, and priorities related to the intervention. Trained community leaders acted as seeds in recruiting interviewees. | 166 participants completed structured assessments at the beginning of the study and a 12-month follow-up (24 months after the start of the study). Empowering and using community leaders to screen and follow up with MSM in the testing process is extremely effective in improving testing rates. Immigrants viewed community leaders they did not identify with suspicion. Lack of proximity to health services and providers was seen as a barrier to testing. | Training and engaging community leaders can significantly increase HIV testing rates by overcoming structural barriers and personal beliefs. |

| Solorio, et al. 2013 [15] | To evaluate the attitudes and beliefs about HIV testing among immigrant Latin men who have sex with men (MSM) who do and do not get tested. | A qualitative study was conducted with 54 Latin immigrant MSM in Seattle, Washington in 2010. | The main obstacle to HIV testing among this sample of immigrants was fear of receiving a positive result, according to both groups (testers and non-testers). They reported negative attitudes toward the possible results of HIV tests with regard to their communities and believed that the presence of Latinx staff at testing sites could compromise confidentiality and therefore decrease their trust in the healthcare system. In addition, they expressed concern about the cost of testing. | Campaigns on radio, television, and the internet should be tailored to the language and should reduce fear of HIV testing by including free locations with empathetic professionals. |

| Spadafino et al. [16] |

To assess the effect of sociodemographic, personal, and behavioral factors on HIV testing. | A telephone survey was conducted with 176 MSM, accompanied by a focus group of 40 MSM in New York City. | Spanish-only speakers were less likely to get tested. Higher educational levels and younger age positively influenced testing rates. Perceived immigration status issues (legal or illegal immigrant status; perception of their rights) can influence the decision to get tested. Socioeconomic and behavioral factors can intensify these obstacles. | Language and immigration-related barriers (irregularity and lack of knowledge of service dynamics) influence the chance of testing. |

| Lee, 2019 [17] |

To assess the effect of the migration process on HIV testing. | A descriptive and qualitative study was conducted using semi-structured interviews with 34 Latino immigrants in New York City. | The migration process seems to subject Latino immigrant MSM to situations of cumulative stress and trauma, resulting in emotional, psychological, and behavioral consequences. In the short and long term, this lowered their motivation to undergo HIV testing and posed significant barriers to testing. | Strategies should be designed to reduce the stress related to immigration and facilitate the engagement of Latino MSM with healthcare services. |

| Oster 2013 [18] |

To assess the effect of birthplace on HIV testing among immigrants. | A cross-sectional, quantitative study was conducted with 1,734 Latinx individuals to evaluate testing within the last 12 months. | The main reasons cited for not getting tested were a false sense of being at low risk for HIV, fear of a positive result (31%), and fear and concerns related to HIV stigma, including fear of someone finding out the results and their name being reported to the government, or losing their job, insurance, or home. MSM who have lived/immigrated for a longer time tend to be tested more easily. Services should try more efficient strategies to screen individuals who have recently migrated. | Services should try more efficient screening strategies for individuals who have recently migrated. |

| Joseph et al, 2014 [19] |

Evaluate HIV testing among sexually active Hispanic/Latino MSM in Miami-Dade County. | Quantitative study with 608 sexually active Latino MSM residing in Miami-Dade County and New York City. | The most frequently reported reason for not getting tested was fear of a positive result for HIV. The longer the time since their last test, the higher the reported fear of the result. Confidentiality of the result, lack of access to healthcare services, and low-risk perception were more common among those who had been tested less than 5 years ago. | Several factors influence the willingness to get tested, but attention should be paid to the formulation of public policies regarding differences in acculturation, English proficiency, immigration status, country of origin, and length of stay in the United States. |

| Lee and Yu, 2019. [20] |

Compare HIV testing among documented and undocumented immigrants. | A descriptive study, in the form of a survey, was conducted in 2017 in New York City with two groups of 301 Latino immigrant men who have sex with men (MSM), documented and undocumented. | Undocumented immigrants reported lower levels of education and literacy, as well as lower income and lack of health insurance compared to documented immigrants, which negatively impacted HIV testing. Therefore, immigration status or the manner of entry into the country should be considered in the formulation of strategies to improve testing. | Documental barriers represent challenges in accessing healthcare services and HIV testing. |

| Ramírez-Ortiz et al 2021 [21] |

To estimate the prevalence and associated factors of HIV testing self-evaluation before and after immigration. | A cross-sectional study was conducted with data from 504 Latino immigrants residing in Florida, United States. | HIV testing was more common before (56.7%) than after immigration (23.8%), indicating that being a migrant has an impact on the willingness to get tested and seek testing. The chances of testing after immigration increased for those who had health insurance and a regular healthcare provider after immigration and for those who had previously tested for HIV before immigration. On the other hand, the prevalence ratio for testing was lower for immigrants who engaged in high-risk sexual behaviors, such as unprotected sex in the three months before immigration. | Testing for HIV before or at the beginning of the immigration process may facilitate connection with HIV prevention and treatment services for immigrants. |

| Olshefsky et al, 2007 [22] |

To evaluate the effect of a Spanish-language social marketing campaign on Latino MSM in California | An 8-week intervention was implemented using various media such as radio, print media, a website, and a toll-free hotline for HIV testing referrals. The campaign focused on high-risk groups for HIV, including cross-border migrants, rural workers, young sex workers, and MSM. | An increase in documented HIV testing at partner clinics was recorded during the study, suggesting that language can be an important barrier to HIV testing that can be overcome by community campaigns. There appears to be a relationship between testing and seasonal fluctuations in immigration for work in rural areas. | Using mass media coupled with culturally adapted language and immigrants' root language can facilitate adherence to HIV testing. |

| Barrington et al, 2018 [23] |

To understand the gaps related to HIV testing in Latin. | A qualitative study with nine key informants from community services in North Carolina, United States. | Dialogue about sexual behavior among Latinx immigrants was infrequent and superficial, and discussions about “protecting oneself” did not delve into the details of real experiences with risky sexual behavior, unprotected sex, condom use, and HIV testing. The experience of migration creates difficulties in approaching HIV testing as a routine matter, making it challenging to engage this population. | For network approaches to promoting HIV testing to be effective, it is critical to comprehend and address the social, political, and geographic context within which social networks operate. |

| Painter et al, 2019 [24] |

To evaluate the effect of social support on HIV testing. | This is a randomized study involving 304 Latino MSM in North Carolina, United States, | Refined statistical analysis revealed that several factors influenced HIV testing, including general and HIV-related social support, immigrant acculturation, attachment to the gay community, knowledge about HIV and other STIs, and higher education. On the other hand, strong adherence to traditional Hispanic/Latino notions and values of masculinity, as well as being a Spanish speaker/proficient only, were identified as barriers to testing. | Social support and the relationships that generate and maintain it can serve as a valuable resource for HIV prevention among these populations. |

| Solorio et al, 2016 [25] |

Describe the evaluation of a pilot multimedia testing campaign for HIV. | This is a cohort follow-up study with 50 young Latino immigrant MSM. In the study design, interviews were scheduled 3 months before the campaign (baseline interview), 3 months during the campaign, and 2 months after the campaign. | Attitudes, beliefs, cultural norms, and self-efficacy were identified as the main barriers to HIV testing and were improved with community intervention. The intervention had a significant impact on intentions toward HIV testing. | The success of education programs targeted towards populations at risk for HIV/AIDS, such as Latino immigrant MSM, should take into account their unique characteristics, beliefs, emotions, and perceived cultural and structural barriers, and be able to meet their psychosocial needs through strategic and systematic formative evaluation processes. |

| Horridge et al. 2019 [26] |

Understand and identify the barriers that Latino immigrant MSM perceive in getting HIV testing. | Descriptive and analytical study with 128 Latino immigrants MSM. | Approximately one-third of the participants reported moderate or high levels of barriers to HIV testing. A series of factors were cited as barriers, with the most common being “lack of knowledge about where to get tested,” while “not having health insurance” and “fear of a positive test result” ranked second and third. Other identified barriers included practicing safe sex and perceiving testing as unnecessary, as well as not receiving a recommendation for testing from healthcare professionals. Significant factors associated with barriers to HIV testing in the bivariate analysis were speaking only Spanish and being unemployed. In the multivariate analysis, speaking only Spanish, being unemployed, and adhering to traditional notions of masculinity were associated with higher levels of barriers to HIV testing. | To address barriers to HIV testing in Latino immigrant MSM, educational programs should be tailored to the specific beliefs and needs of this population, particularly with regard to their culture, language, employment status, and cultural beliefs surrounding masculinity. |

4. DISCUSSION

Latin immigrant MSMs tend to have lower rates of HIV testing compared to non-immigrant MSMs or the general population [9-11]. This low testing rate can be influenced by various factors, including knowledge and awareness about HIV [18, 26]; stigma, discrimination, and lack of confidence in health services [15, 16, 19, 24, 26]; barriers to access to healthcare [22, 25, 26]; type of partnerships and relationships; lack of knowledge about their rights [16, 17, 20]; status related to migration and documentation [16, 17, 20], and personal, cultural, and religious beliefs [14, 16, 18, 19, 26].

4.1. Barriers to HIV Testing

The challenges faced by healthcare systems and services in addressing MSM in their new countries have a significant impact on testing rates [9-11]. While HIV testing efforts have gained momentum among women, particularly through primary care services such as prenatal care, similar entry points have not been identified for the male population. This lack of identified entry points significantly hampers their trust in healthcare services and, consequently, their acceptance of HIV testing [19, 21-23, 25]. From a public policy perspective, there is a gap in strategies aimed at preventing HIV in this vulnerable population.

Moreover, cultural factors related to patriarchy, stereotypes, and the promotion of hegemonic and toxic masculinity in Western societies create an unwelcoming environment for open discussions about sexuality, safe sex, risk identification, HIV prevention, access to healthcare, and adherence to treatment among men [8-26]. This environment becomes even more challenging for MSM due to issues of gender and stigma [15, 21, 22]. Age markers, such as being over 50 years old, further exacerbate the situation as it leads to triple invisibility related to age, immigration status, and sexual orientation, resulting in a lack of discussion about the sexual health of MSM over 50 [16, 18].

Some of the texts examined in this review highlight the difficulties faced by immigrants in obtaining healthcare services, particularly due to the illegality of their immigration status or long-term residence in the new country. Immigrants often refrain from seeking preventive measures out of fear of discovery and punishment by the country's legal system. Fear of deportation is associated with a lack of coverage or health insurance and limited access to healthcare services among undocumented immigrants [21, 26]. Undocumented immi-grants may also encounter discrimination and stigma in healthcare settings, further discouraging them from seeking care. In such cases, it is crucial to establish specialized services for this population, regardless of their residence status [16-18, 20, 23].

Opportunities for HIV testing among key populations have been missed. Countries must make continuous efforts to incorporate strategies such as HIV screening, particularly within primary healthcare services, to increase the proportion of the population undergoing testing [21-27]. It is believed that the MSM population in immigration contexts can be better reached through the expansion of HIV self-testing as part of combined prevention strategies [28].

Furthermore, enhancing knowledge and awareness about HIV is crucial in addressing the cultural and healthcare barriers that hinder HIV testing among Latinx immigrants. These barriers include concerns about their rights, fears related to documentation status [18], limited accessibility [25], anxiety over test results [14, 19, 21, 23-26], language barriers [16, 24, 26], community and personal prejudice towards seeking testing [15, 26], cost concerns [21, 25, 26], and limited access to healthcare [15, 19, 23, 25].

Our findings also highlight that Latinx immigrants often experience repeated stress and trauma throughout the immigration process, resulting in significant emotional and psychological consequences that further contribute to barriers to HIV testing. These individuals tend to avoid activities deemed stressful [14-25], including gaining awareness of their serological status. This issue may also intersect with other phenomena, such as religious social capital and social support systems among immigrants, particularly those who are undocumented [29].

4.2. Facilitators for HIV Testing

The level of knowledge and awareness about HIV among Latinx immigrants has a significant influence on their decision to undergo testing, as revealed by our findings. Increasing literacy and understanding of HIV transmission mechanisms and associated risk factors can enhance individuals' perception of vulnerability to the virus and boost their self-efficacy in managing their health. This, in turn, can motivate them to seek testing and adopt effective preventive measures to safeguard their well-being and that of their partners [16, 24]. Consequently, promoting widespread knowledge of HIV serostatus, particularly through health promotion initiatives [30, 31] and the utilization of artificial intelligence in surveillance systems for testing monitoring [32], can yield positive implications for MSM in the context of international migration. Similarly, enhanced knowledge about HIV and testing can facilitate linking MSM to treatment [33].

To effectively address the unique challenges and barriers faced by Latinx MSM in HIV testing, it is essential to adopt a culturally sensitive and individualized approach that acknowledges their specific vulnerabilities, which are often compounded by unique cultural, linguistic, and social factors influencing their willingness to seek and undergo testing [19-23]. This study underscores the importance of targeted campaigns [25] and highlights the need for investments in robust data collection to better understand the problem, enhance engagement in the adoption of combined prevention strategies, optimize navigation within healthcare networks and services, streamline consultations, adjust service provisions (including location, operating hours, and transportation), and monitor tested cases [34].

Building a relationship of trust is paramount to addressing the prevailing distrust [15, 19, 23] towards healthcare services among Latinx immigrants. Healthcare professionals play a pivotal role in mitigating specific barriers, particularly those associated with confidentiality and stigma. Providing testing in a confidential and private setting can significantly alleviate fears of stigma and discrimination, ultimately promoting more frequent testing, especially among those with health insurance [21]. Moreover, studies in the field highlight the imperative of adopting a biobehavioral approach that encompasses various domains of study, such as health and law, with the goal of centralizing care for Latinx sexual and gender minorities, aiming to transcend the cultural influences of migration on HIV risk [35, 36].

Empowering Latinx immigrant MSM through the establishment of peer-led initiatives that promote HIV testing constitutes a vital strategy for fostering trust, enhancing awareness, and facilitating prevention and treatment efforts for HIV/AIDS [16, 24, 25]. This approach also affords the opportunity to provide testing in non-traditional community-based settings, such as churches, community centers, or mobile clinics, thereby improving accessibility and reducing barriers. Furthermore, it is important to recognize that the implementation and continuation of public policies aimed at HIV prevention can have a positive impact on the generational aspect of migration. This is because not only the migrant population stands to benefit, but also their descendants, who may enjoy greater access to healthcare resources, knowledge about HIV and its non-transmission, and awareness of AIDS. By consistently targeting testing services and centers toward this population, their descendants can reap the advantages of these ongoing initiatives [37].

5. LIMITATIONS

This study has several notable limitations. Firstly, the included studies exhibit a wide range of diversity, which hinders the ability to provide a more precise overview of the barriers. Secondly, the absence of experimental or quasi-experimental studies, such as community clinical trials, limits our ability to identify specific factors that effectively promote engagement and increase testing rates within this population. These types of studies would offer valuable insights into causation. Thirdly, due to methodological restrictions, only twelve studies were eligible for inclusion. This small number of studies may limit the comprehensiveness and generalizability of the findings. Lastly, a more nuanced understanding of the countries of origin of the immigrants would enable more targeted and effective global health interventions. However, the studies often utilize the term “Latinos” in a broad and generic manner, which impedes the ability to tailor interventions based on specific regional or cultural factors.

CONCLUSION

Interventions targeted at increasing HIV testing among Latin immigrants, whether implemented locally, nationally, or internationally, have a greater chance of success when they directly confront the root causes that deter individuals from seeking testing. It is essential to develop these interventions while considering the distinct needs and characteristics of immigrant MSM. Achieving higher HIV testing rates among Latin immigrants necessitates a comprehensive approach that acknowledges and addresses the unique challenges encountered by this population. By effectively targeting these challenges and tailoring interventions to cater to the specific requirements of Latino immigrants, it is possible to enhance testing rates and, ultimately, mitigate the transmission of HIV.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

STANDARDS OF REPORTING

PRISMA guidelines and methodology were followed.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The data and supportive information are available within the article.

FUNDING

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest financial or otherwise.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

PRISMA checklist is available as supplementary material on the publisher’s website along with the published article.

REFERENCES

| [1] | Assefa Y, Gilks CF. Ending the epidemic of HIV/AIDS by 2030: Will there be an endgame to HIV, or an endemic HIV requiring an integrated health systems response in many countries? Int J Infect Dis 2020; 100: 273-7. |

| [2] | UNAIDS, Global HIV statistics. 1989. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/UNAIDS_FactSheet_en.pdf |

| [3] | Danwang C, Noubiap JJ, Robert A, Yombi JC. Outcomes of patients with HIV and COVID-19 co-infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Res Ther 2022; 19(1): 3. |

| [4] | Pineda JR. Vulnerability to hiv/aids in gay and bisexual individuals during migration: The case of Colombian immigrants residing in spain. Saude Soc 2020; 29(3): 1-12. |

| [5] | Maharani J, Seweng A, Sabir M, et al. Sexual behavior influence against HIV/AIDS in homosexuals at Palu City in 2020. Gac Sanit 2021; 35(35)(Suppl. 2): S135-9. |

| [6] | Dunbar W, Pape JW, Coppieters Y. HIV among men who have sex with men in the Caribbean: Reaching the left behind. Pan Am J Public Heal 2021; 45: 1-7. |

| [7] | Philbin MM, Hirsch JS, Wilson PA, Ly AT, Giang LM, Parker RG. Structural barriers to HIV prevention among men who have sex with men (MSM) in Vietnam: Diversity, stigma, and healthcare access. PLoS One 2018; 13(4): e0195000. |

| [8] | Cota VL, Marques Da Cruz M. Barreiras de acesso para Homens que fazem Sexo com Homens à testagem e tratamento do HIV no município de Curitiba (PR) Access barriers for Men who have Sex with Men for HIV testing and treatment in Curitiba (PR). Fundação Oswaldo Cruz 2021; 45(129): 393-405. |

| [9] | Peters CMM, Dukers-Muijrers NHTM, Evers YJ, Hoebe CJPA. Barriers and facilitators to utilisation of public sexual healthcare services for male sex workers who have sex with men (MSW-MSM) in The Netherlands: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health 2022; 22(1): 1398. |

| [10] | Dinglasan JLG, Rosadiño JDT, Pagtakhan RG, et al. ‘Bringing testing closer to you’: barriers and facilitators in implementing HIV self-testing among Filipino men-having-sex-with-men and transgender women in National Capital Region (NCR), Philippines – a qualitative study. BMJ Open 2022; 12(3): e056697. |

| [11] | Ross J, Cunningham CO, Hanna DB. HIV outcomes among migrants from low-income and middle-income countries living in high-income countries. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2018; 31(1): 25-32. |

| [12] | Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021; 372(71): n71. |

| [13] | Morgan RL, Whaley P, Thayer KA, Schünemann HJ. Identifying the PECO: A framework for formulating good questions to explore the association of environmental and other exposures with health outcomes. Environ Int 2018; 121(Pt 1): 1027-31. |

| [14] | Rhodes SD, Alonzo J, Mann-Jackson L, et al. A peer navigation intervention to prevent HIV among mixed immigrant status Latinx GBMSM and transgender women in the United States: outcomes, perspectives and implications for PrEP uptake. Health Educ Res 2020; 35(3): 165-78. |

| [15] | Solorio R, Forehand M, Simoni J. Attitudes towards and beliefs about HIV testing among Latino immigrant MSM: A comparison of testers and nontesters. AIDS Res Treat 2013; 2013: 563537. |

| [16] | Spadafino JT, Martinez O, Levine EC, Dodge B, Muñoz-Laboy M, Fernandez MI. Correlates of HIV and STI testing among Latino men who have sex with men in New York City. AIDS Care 2016; 28(6): 695-8. |

| [17] | Lee JJ. Cumulative Stress and Trauma from the Migration Process as Barriers to HIV Testing: A Qualitative Study of Latino Immigrants. J Immigr Minor Health 2019; 21(4): 844-52. |

| [18] | Oster AM, Russell K, Wiegand RE, et al. HIV infection and testing among Latino men who have sex with men in the United States: the role of location of birth and other social determinants. PLoS One 2013; 8(9): e73779. |

| [19] | Joseph HA, Belcher L, O’Donnell L, Fernandez MI, Spikes PS, Flores SA. HIV testing among sexually active Hispanic/Latino MSM in Miami-Dade County and New York City: opportunities for increasing acceptance and frequency of testing. Health Promot Pract 2014; 15(6): 867-80. |

| [20] | Lee JJ, Yu G. HIV testing, risk behaviors, and fear: A comparison of documented and undocumented latino immigrants. AIDS Behav 2019; 23(2): 336-46. |

| [21] | Ramírez-Ortiz D, Forney DJ, Sheehan DM, Cano MÁ, Romano E, Sánchez M. Pre- and Post-immigration HIV Testing Behaviors among Young Adult Recent Latino Immigrants in Miami-Dade County, Florida. AIDS Behav 2021; 25(9): 2841-51. |

| [22] | Olshefsky AM, Zive MM, Scolari R, Zuñiga ML. Promoting HIV risk awareness and testing in Latinos living on the U.S.-Mexico border: the Tú No Me Conoces social marketing campaign. AIDS Educ Prev 2007; 19(5): 422-35. |

| [23] | Barrington C, Gandhi A, Gill A, Villa Torres L, Brietzke MP, Hightow-Weidman L. Social networks, migration, and HIV testing among Latinos in a new immigrant destination: Insights from a qualitative study. Glob Public Health 2018; 13(10): 1507-19. |

| [24] | Painter TM, Song EY, Mullins MM, et al. Social Support and Other Factors Associated with HIV Testing by Hispanic/Latino Gay, Bisexual, and Other Men Who Have Sex with Men in the U.S. South. AIDS Behav 2019; 23(S3)(Suppl. 3): 251-65. |

| [25] | Solorio R, Norton-Shelpuk P, Forehand M, et al. Tu amigo pepe: Evaluation of a multi-media marketing campaign that targets young latino immigrant MSM with HIV testing messages. AIDS Behav 2016; 20(9): 1973-88. |

| [26] | Horridge DN, Oh TS, Alonzo J, et al. Barriers to HIV testing within a sample of spanish-speaking latinx gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men: Implications for HIV prevention and care. Health Behav Res 2019; 2(3): 139-48. |

| [27] | Patel D, Williams WO, Heitgerd J, Taylor-Aidoo N, DiNenno EA. Estimating gains in HIV testing by expanding HIV screening at routine checkups. Am J Public Health 2021; 111(8): 1530-3. |

| [28] | Vasconcelos R, Avelino-Silva VI, de Paula IA, et al. HIV self-test: a tool to expand test uptake among men who have sex with men who have never been tested for HIV in São Paulo, Brazil. HIV Med 2022; 23(5): 451-6. |

| [29] | Sanchez M, Diez S, Fava NM, et al. Immigration stress among recent latino immigrants: The protective role of social support and religious social capital. Soc Work Public Health 2019; 34(4): 279-92. |

| [30] | Vazquez V, Rojas P, Cano MÁ, De La Rosa M, Romano E, Sánchez M. Depressive symptoms among recent Latinx immigrants in South Florida: The role of premigration trauma and stress, postimmigration stress, and gender. J Trauma Stress 2022; 35(2): 533-45. |

| [31] | Alwano MG, Bachanas P, Block L, et al. Increasing knowledge of HIV status in a country with high HIV testing coverage: Results from the Botswana Combination Prevention Project. PLoS One 2019; 14(11): e0225076. |

| [32] | Patel D, Johnson CH, Krueger A, et al. Trends in HIV Testing Among US Adults, Aged 18–64 Years, 2011–2017. AIDS Behav 2020; 24(2): 532-9. |

| [33] | Abubakari GMR, Turner D, Ni Z, et al. Community-Based Interventions as Opportunities to Increase HIV Self-Testing and Linkage to Care Among Men Who Have Sex With Men – Lessons From Ghana, West Africa. Front Public Health 2021; 9(June): 660256. |

| [34] | Rosas M, Moreno S. Global strategy in the treatment of HIV infection in 2022. Rev Esp Quimioter 2022; 35(Suppl 3)(Suppl. 3): 34-6. |

| [35] | Martinez O. A review of current strategies to improve HIV prevention and treatment in sexual and gender minority Latinx (SGML) communities. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2021; 19(3): 323-9. |

| [36] | Aidoo-Frimpong G, Agbemenu K, Orom H. A Review of Cultural Influences on Risk for HIV and Culturally-Responsive Risk Mitigation Strategies Among African Immigrants in the US. J Immigr Minor Health 2021; 23(6): 1280-92. |

| [37] | Konkor I, Luginaah I, Husbands W, et al. Immigrant generational status and the uptake of HIV screening services among heterosexual men of African descent in Canada: Evidence from the weSpeak study. Journal of Migration and Health 2022; 6(April): 100119. |