All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Prevalence and Patterns of Antiretroviral Therapy Prescription in the United States

Abstract

Background:

The use of Antiretroviral Therapy (ART) in HIV-infected persons has proven to be effective in the reduction of risk of disease progression and prevention of HIV transmission.

Objective:

U.S. Antiretroviral Therapy (ART) guidelines specify recommended initial, alternative initial, and not-recommended regimens, but data on ART prescribing practices and real-world effectiveness are sparse.

Methods:

Nationally representative annual cross sectional survey of HIV-infected adults receiving medical care in the United States, 2009-2012 data cycles. Using data from 18,095 participants, we assessed percentages prescribed ART regimens based on medical record documentation and the associations between ART regimens and viral suppression (most recent viral load test <200 copies/ml in past year) and ART-related side effects.

Results:

Among HIV-infected adults receiving medical care in the United States, 91.8% were prescribed ART; median time since ART initiation to interview date was 9.8 years. The percentage prescribed ART was significantly higher in 2012 compared to 2009 (92.7% vs 88.7%; p < 0.001). Of those prescribed ART, 51.6% were prescribed recommended initial regimens, 6.1% alternative initial regimens, 29.0% not-recommended as initial regimens, and 13.4% other regimens. Overall, 79.5% achieved viral suppression and 15.7% reported side effects. Of those prescribed ART and initiated ART in the past year, 80.5% were prescribed recommended initial regimens.

Conclusion:

Among persons prescribed ART, the majority were prescribed recommended initial regimens. Monitoring of ART use should be continued to provide ongoing assessments of ART effectiveness and tolerability in the United States.

1. INTRODUCTION

Antiretroviral Therapy (ART) is recommended for all HIV-infected persons to reduce the risk of disease progression and prevent HIV transmission [1]. By 2017, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved more than 26 Individual Antiretroviral (ARV) medications in seven mechanistic classes and several fixed-dose combinations to treat HIV infection [2]. To help clinicians select efficacious, safe and tolerable regimens, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) guidelines specify three categories of initial ARV regimens for ART-naïve adult patients: recommended, alternative, and not-recommended [1]. As of December 2014, the ten recommended initial regimens have optimal and durable efficacy, favorable tolerability and toxicity profiles, and ease of use. The nine alternative regimens are effective and tolerable but have potential disadvantages when compared with recommended initial regimens. Lastly, 17 regimens are listed that include ARVs not-recommended as initial therapy due to concerns about efficacy, safety or tolerability.

While guideline-specified ARV regimens have been well-studied in research settings in ART-naïve populations [3-9], little is known about HIV providers’ prescribing practices and the real-world effectiveness of these regimens in the United States. In practice, ART prescribing and effectiveness could be different from that seen in clinical trials or cohort studies, as ARVs may be used in different populations and settings, and for longer periods of time. We used data from the Medical Monitoring Project (MMP), a nationally representative sample of HIV-infected adults receiving medical care in the United States to obtain population-based estimates of ART prescribing patterns, including the overall percentage of patients prescribed guideline-specified ART as well as specific ARV medications and regimens.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. MMP Study Design

MMP is an HIV surveillance system that uses an annual, complex-sample, cross-sectional design to produce nationally representative estimates of behavioral and clinical characteristics of HIV-infected adults receiving medical care in the United States [10-12]. For the 2009-2012 data collection cycles, first U.S. states and territories were sampled, then facilities providing HIV care, and finally adults aged ≥18 years receiving at least one medical care visit in participating facilities between January and April of the data collection year. For state and territory samples, probability of selection was proportionate to AIDS prevalence; for provider samples, probability of selection was proportionate to HIV-infected patient census. Data were collected annually from June 2009 to May 2013 via patient interviews and medical record abstractions.

MMP data cycles (2009-2012) includes 17 states or territories, which contain about 73% of all persons living with HIV in the United States [13]. The number of eligible facilities sampled in 2009-2012 data cycles ranged from 603 in 2009 to 548 in 2012. Among those sampled, 461 in 2009 to 467 in 2012 facilities participated, resulting in a mean facility-level response rate of 76.5% for 2009 and 85.2% in 2012. Most of the HIV care facilities sampled were private practices (48%), followed by hospital-based facilities (24%) and community health centers (15%). The remainder facilities were clinical research facilities (8%), state or local health department clinics (5%), community-based service organizations (4%), and Veterans Administration facilities (3%).

Of nearly 9,400 sampled persons per data cycle, completed interview and linked medical record abstraction data ranged from 4,217 in 2009 to 5,119 in 2012. All sampled states and territories participated in MMP and the mean facility-level and patient-level response rates for matched interview and medical record data were 82% and 54%, respectively. All data were weighed based on known probabilities of selection at state or territory, facility, and patient levels and adjusted for non-response using predictors of patient-level response including facility size, facility type (public or private), race/ethnicity, time since HIV diagnosis, and age.

2.2. Primary Study Variables

2.2.1. ART prescription and ARV regimen classifications

Documentation of ART prescription during the year prior to interview was abstracted from the medical records of MMP participants. Visit dates were used to determine the most recent ART prescription preceding the interview date; individual ARVs were combined into specific ARV regimens, which were grouped into DHHS guideline-specified initial regimen categories (based on December 2014 version of guidelines as a reference for comparisons for regimen types): recommended, alternative, and not-recommended as initial regimens [1]. Regimens not on the DHHS list were classified as other.

2.2.2. ART initiation

Self-reported dates of first ART use were provided during interviews. Using these dates, we examined ART initiation in the past year (recent ART initiation), those who initiated ART more than 1 year ago, and those with unknown ART initiation dates.

2.2.3. Clinical measures

To further examine ART prescription patterns, additional clinical measures were examined by ART regimens: 1) recent viral suppression defined as the most recent plasma HIV viral load test in the past year documented in the medical record as undetectable or <200 copies/ml; 2) durable viral suppression defined as all plasma HIV viral load tests in the past year documented in the medical record as undetectable or <200 copies/ml; 3) self-reported dose adherence in the 72 hours prior to the interview; and 4) self-reported ART-related side effects in the 30 days prior to the interview. A patient was considered adherent if they were currently taking ART and if they were adherent to taking all doses (i.e., taking a dose or set of pills/spoonfuls/injections of ART medications as prescribed by a medical provider). If both conditions did not apply, a patient was considered not adherent.

2.2.4. Covariates

To explore the associations between ARV prescription and regimens compared to selected variables, we examined several potential correlates, including demographic and behavioral variables obtained via interview and clinical variables obtained via medical record abstraction or interview. Demographic characteristics included age at interview, gender, race/ethnicity, country or territory of birth, educational level, poverty level, homelessness, incarceration, type of health insurance and coverage. Behavioral characteristics included non-injection drug use for non-medical reasons, binge drinking (≥5 drinks per day for men, ≥4 drinks per day for women in the past 30 days), and tobacco use. Clinical factors obtained via interview included depression, with severity calculated using an established algorithm [14, 15], time since HIV diagnosis, and time since ART initiation. Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) diagnosis and CD4+ T-lymphocyte cell (CD4) counts were abstracted from medical records. Disease stage was defined according to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) surveillance definitions: Stage 1, no AIDS and nadir CD4 count ≥ 500 cells/µL (or CD4% ≥ 29); Stage 2, no AIDS and nadir CD4 count 200-499 cells/µL (or CD4% 14-<29); Stage 3, AIDS or nadir CD4 count 0-199 cells/µL (or CD4% <14) [16].

2.3. Statistical Analysis

First, we calculated weighted percentages and 95% Confidence Intervals (CIs) for all categorical variables. Medians and Interquartile Ranges (IQRs) were computed for continuous variables. We examined the bivariate associations of those who had been prescribed ART compared to those who had not prescribed ART with potential covariates. The Rao-Scott chi-square test [17] was used to test for differences between groups.

Next, we estimated the weighted prevalence of use of each of the ARV regimens. We described the different clinical characteristics among the ARV regimen classifications and estimated the percentages of participants who had recent viral suppression, durable (all measures) suppression, were dose adherent, and had side effects for all persons who were prescribed ART and those who had initiated ART in the past year.

Furthermore, we examined differences in characteristics between participants who had recent ART initiation to those who initiated ART more than a year ago and estimated the prevalence of ARV regimens among participants who had recent ART initiation. A large number of participants (12.4%) among those were prescribed ART were excluded from the ART initiation analyses due to missing ART entry dates. To assess the impact of excluding participants with missing ART initiation dates, we completed a sensitivity analysis to compare the socio-demographic characteristics of those with and without ART initiation dates.

Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS (version 9.3, SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina) and SUDDAN (version 11.0.0, RTI International, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina), and accounted for complex sample survey design. Hypothesis testing results with p-values < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

2.4. Ethics Statement

In accordance with the federal human subjects protection regulations, MMP was determined to be a non-research, public health surveillance activity used for disease control program or policy purposes [18, 19]. As such, MMP was not subject to federal institutional review board review and received approval for its protocol from CDC officials who were not involved [18]. If required locally, participating states or territories and facilities obtained local institutional review board approval.

3. RESULTS

3.1. ARV Prescription And Regimens

Of 18,905 MMP participants in 2009-2012 data cycles 16,528 (91.1%) were prescribed ART in the year prior to interview. Of persons prescribed ART, the majority were male, aged 40 years or older, non-Hispanic black or non-Hispanic white, lived above the poverty level, and diagnosed with HIV ≥10 years ago (Table 1). Although, 71.6% of persons had AIDS (Stage 3), almost half (47.7%) had a geometric mean CD4 count ≥500 cells/µL in the past 12 months. Of persons prescribed ART, 79.5% achieved recent viral suppression, 65.5% achieved durable viral suppression, 84.4% reported being adherent with all ART doses in the 72 hours prior to interview, and 15.7% reported being troubled by ARV-related side effects in the 30 days prior to interview. Persons who were not prescribed ART were more likely to have experienced homelessness or incarceration, used non-injection drugs, be binge drinkers, current smokers, or had depression in the past 2 weeks than those who were prescribed ART.

| - | Total | Prescribed ART | Not prescribed ART | p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | na | % (CI)b | na | % (CI)b | na | % (CI)b | ||

| Total | 18095 | 100 | 16528 | 91.1 (90.5–91.6) | 1567 | 8.9 (8.4–9.5) | ||

| Age at interview (in years) | <0.001 | |||||||

| 18-29 | 1343 | 7.6 (6.9-8.4) | 1086 | 6.7 (6.0-7.3) | 257 | 17.4 (14.3-20.6) | ||

| 30-39 | 2841 | 16.0 (15.3-16.7) | 2517 | 15.6 (14.8-16.3) | 324 | 20.5 (18.0-23.0) | ||

| 40-49 | 6396 | 35.1 (34.2-35.9) | 5882 | 35.3 (34.5-36.2) | 514 | 32.7 (29.6-35.7) | ||

| ≥ 50 | 7515 | 41.3 (40.4-42.2) | 7043 | 42.5 (41.5-43.4) | 472 | 29.4 (26.3-32.5) | ||

| Gender | 0.001 | |||||||

| Male | 13060 | 72.4 (70.0-74.8) | 12001 | 72.8 (70.5-75.1) | 1059 | 68.3 (64.1-72.5) | ||

| Female | 4780 | 26.2 (23.9-28.6) | 4294 | 25.8 (23.5-28.1) | 486 | 30.5 (26.5-34.5) | ||

| Transgender | 249 | 1.4 (1.2-1.6) | 228 | 1.4 (1.2-1.6) | 21 | 1.2 (0.6-1.7) | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | <0.001 | |||||||

| Non-Hispanic black | 7476 | 41.4 (34.8-48.0) | 6721 | 40.7 (34.0-47.4) | 755 | 48.1 (41.1-55.0) | ||

| Hispanic or Latinoc | 3890 | 19.4 (15.2-23.6) | 3579 | 19.4 (15.1-23.7) | 311 | 19.0 (15.5-22.5) | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 5894 | 34.5 (29.3-39.7) | 5475 | 35.1 (29.9-40.4) | 419 | 27.5 (21.4-33.7) | ||

| Otherd | 821 | 4.8 (4.1-5.5) | 742 | 4.7 (4.0-5.4) | 79 | 5.4 (3.7-7.1) | ||

| Foreign Born | 0.220 | |||||||

| Born in United States | 15696 | 86.6 (85.1-88.1) | 14324 | 86.5 (85.0-88.0) | 1372 | 87.4 (85.0-89.9) | ||

| Born Outside United States | 2392 | 13.4 (11.9-14.9) | 2198 | 13.5 (12.0-15.0) | 194 | 12.6 (10.1-15.0) | ||

| Education Attainment | 0.350 | |||||||

| <High School | 3976 | 21.0 (19.2-22.9) | 3644 | 21.2 (19.2-23.1) | 332 | 19.4 (17.2-21.6) | ||

| High School Diploma or Equivalent | 4935 | 27.0 (25.4-28.6) | 4504 | 26.9 (25.3-28.5) | 431 | 27.5 (25.0-30.1) | ||

| >High school | 9177 | 52.0 (48.8-55.1) | 8374 | 51.9 (48.7-55.1) | 803 | 53.1 (49.4-56.8) | ||

| Poverty Levele in P12M | 0.003 | |||||||

| Above Poverty Level | 9426 | 53.8 (50.8-56.8) | 8659 | 54.1 (51.1-57.1) | 767 | 50.4 (46.3-54.5) | ||

| At or Below Poverty Level | 8059 | 42.7 (39.9-45.5) | 7330 | 42.5 (39.7-45.3) | 729 | 44.8 (40.9-48.8) | ||

| Unknown | 610 | 3.5 (2.9-4.1) | 539 | 3.4 (2.8-4.0) | 71 | 4.8 (3.4-6.1) | ||

| Homeless in P12M | 1520 | 8.3 (7.6-8.9) | 1328 | 7.9 (7.2-8.6) | 192 | 11.6 (9.8-13.4) | <0.001 | |

| Incarcerated in P12M | 907 | 5.1 (4.7-5.6) | 793 | 5.0 (4.5-5.4) | 114 | 6.8 (5.6-8.0) | <0.001 | |

| Type of Health Insurance in P12M | <0.001 | |||||||

| Any Private Insurance | 5360 | 31.0 (27.9-34.2) | 4883 | 30.9 (27.8-34.1) | 477 | 31.9 (27.7-36.1) | ||

| Public Insurance Only | 9246 | 48.9 (46.3-51.5) | 8572 | 49.6 (47.0-52.2) | 674 | 41.3 (37.5-45.2) | ||

| Ryan White Coverage or Uninsured | 3070 | 18.1 (15.5-20.6) | 2694 | 17.4 (14.8-20.0) | 376 | 24.8 (21.1-28.6) | ||

| Other Coverage, Not Unspecified | 355 | 2.0 (1.5-2.5) | 329 | 2.0 (1.5-2.6) | 26 | 1.9 (1.3-2.5) | ||

| Any Non-Injection Drug Use | 4651 | 26.1 (24.7-27.5) | 4116 | 25.3 (23.9-26.6) | 535 | 34.8 (31.7-38.0) | <0.001 | |

| Binge Drinker in Past 30 days | 2863 | 15.7 (15.1-16.3) | 2544 | 15.3 (14.6-15.9) | 319 | 19.8 (17.8-21.9) | <0.001 | |

| Current Smoker | 7371 | 40.8 (39.2-42.4) | 6674 | 40.5 (38.9-42.1) | 697 | 43.9 (41.2-46.6) | 0.005 | |

| Had Depression in Past 2 Weeks | 4063 | 23.0 (21.8-24.2) | 3664 | 22.7 (21.5-23.9) | 399 | 25.8 (22.7-28.9) | 0.025 | |

| Clinical Indicators | ||||||||

| Time since HIV diagnosis (in years) | <0.001 | |||||||

| ≤ 4 | 3787 | 22.1 (21.1-23.1) | 3209 | 20.5 (19.6-21.5) | 578 | 38.4 (34.6-42.2) | ||

| 5-9 | 3862 | 21.3 (20.6-22.0) | 3541 | 21.4 (20.6-22.1) | 321 | 20.1 (17.8-22.3) | ||

| ≥ 10 | 10436 | 56.6 (55.2-58.0) | 9771 | 58.1 (56.8-59.4) | 665 | 41.5 (37.6-45.4) | ||

| Stage of diseasef | <0.001 | |||||||

| Stage 1 (HIV) | 1208 | 7.0 (6.5-7.5) | 910 | 5.8 (5.2-6.3) | 298 | 19.9 (17.9-21.8) | ||

| Stage 2 (HIV) | 4325 | 24.4 (23.5-25.3) | 3685 | 22.7 (21.8-23.6) | 640 | 42.3 (38.3-46.3) | ||

| Stage 3 (HIV and AIDS) | 12494 | 68.6 (67.6-69.6) | 11904 | 71.6 (70.5-72.6) | 590 | 37.9 (34.0-41.7) | ||

| Geometric mean CD4 count (cells/µL) in P12M | <0.001 | |||||||

| 0-199 | 2112 | 11.9 (11.2-12.7) | 2039 | 12.5 (11.6-13.3) | 73 | 5.5 (4.2-6.7) | ||

| 200-349 | 2884 | 16.5 (15.6-17.3) | 2751 | 17.0 (16.1-17.9) | 133 | 10.5 (8.4-12.5) | ||

| 350-499 | 3952 | 23.1 (22.5-23.8) | 3606 | 22.8 (22.1-23.5) | 346 | 26.8 (24.2-29.4) | ||

| 500+ | 8323 | 48.4 (47.3-49.6) | 7581 | 47.7 (46.5-48.9) | 742 | 57.2 (54.6-59.9) | ||

| Viral suppression: most recent viral load < 200 copies/mL or undetectable | 13559 | 74.7 (73.4-76.0) | 13150 | 79.5 (78.3-80.7) | 409 | 25.9 (22.8-29.0) | <0.001 | |

| Durable viral suppression: all viral load in P12M < 200 copies/mL or undetectable | 11218 | 61.6 (60.1-63.1) | 10869 | 65.5 (64.0-66.9) | 349 | 22.1 (19.2-25.1) | <0.001 | |

| Dose adherence in past 3 daysg | 13890 | 84.4 (83.4-85.3) | 13468 | 84.4 (83.5-85.4) | 422 | 81.7 (78.3-85.1) | 0.087 | |

| Reported side effects from ART in past 30 daysg | 2537 | 15.9 (15.0-16.8) | 2433 | 15.7 (14.8-16.5) | 104 | 21.8 (17.2-26.5) | 0.052 | |

| Time since ART Initiation | ||||||||

| ≤1 year ago | 854 | 5.4 (4.9-5.8) | 854 | 5.4 (4.9-5.8) | ||||

| >1 year ago | 13733 | 82.2 (80.9-83.6) | 13733 | 82.2 (80.9-83.6) | ||||

| Unknown/missing | 1941 | 12.4 (11.0-13.7) | 1941 | 12.4 (11.0-13.7) | ||||

| Median ART initiation to interview, in years [IQR] | 14587 | 9.6 [3.9-15.4] | 14587 | 9.6 [3.9-15.4] | ||||

| Survey year | <0.001 | |||||||

| 2009 | 4217 | 23.2 (21.1-25.3) | 3737 | 22.6 (20.5-24.6) | 480 | 29.2 (25.6-32.9) | ||

| 2010 | 4474 | 24.3 (22.0-26.7) | 4077 | 24.1 (21.7-26.5) | 397 | 26.6 (22.8-30.4) | ||

| 2011 | 4503 | 26.3 (24.0-28.6) | 4151 | 26.7 (24.3-29.0) | 352 | 22.7 (18.9-26.4) | ||

| 2012 | 4901 | 26.2 (23.9-28.5) | 4563 | 26.7 (24.4-28.9) | 338 | 21.5 (17.8-25.3) | ||

Among all persons prescribed ART, 51.6% were prescribed recommended initial regimens, 6.1% alternative initial regimens, 29.0% were not-recommended as initial regimens, and 13.4% were classified as other regimens (Table 2). Among all persons prescribed ART, efavirenz (EFV)/tenofovir (TDF)/emtricitabine or lamivudine (XTC) was the most commonly prescribed recommended initial regimen (27.3%), followed by ritonavir-boosted atazanavir (ATVr)/TDF/XTC (11.4%), ritonavir-boosted darunavir (DRVr)/TDF/XTC (4.6%) and raltegravir (RAL)/TDF/XTC (3.5%). Among the most commonly prescribed Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitor (NRTI) backbone regimens, the most recently prescribed in the past 12 months were TDF/XTC (64.8%), abacavir (ABC)/XTC (9.5%) and zidovudine (ZDV)/XTC (5.9%) (Supplemental Table 1). The most commonly prescribed individual ARVs were TDF (72.5%), emtricitabine (FTC) (66.0%), ritonavir (RTV) (44.5%), EFV (34.0%), lamivudine (3TC) (23.0%), ATV (21.6%), ABC (16.4%), RAL (14.6%), DRV (12.6%), lopinavir (LPV) (10.8%) and ZDV (10.2%) (Supplemental Table 2). Very few persons were prescribed non-recommended ARVs, such as stavudine (0.9%).

| DHHS Guideline-Specified ARV Regimen as of December 2014 | n | Prescribed ARV Regimen Col% (CI) | Recent VL Suppressed Row% (CI) |

All VL Suppressed Row% (CI) |

Dose Adherent Row% (CI) |

Reported Side Effects Row% (CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recommended Initial Regimens | 8428 |

51.6 (49.6-53.5) |

81.6 (80.5-82.8) |

66.3 (64.7-67.9) |

86.3 (85.3-87.4) |

14.4 (13.3-15.5) |

| EFV/TDF/XTC | 4370 | 27.3 (26.1-28.4) |

85.4 (84.2-86.5) |

72.6 (70.7-74.5) |

89.5 (88.3-90.6) |

14.1 (12.9-15.3) |

| ATVr/TDF/XTC | 1925 | 11.4 (10.6-12.3) |

75.9 (73.2-78.5) |

58.4 (55.2-61.7) |

83.1 (81.2-85.1) |

14.1 (12.1-16.2) |

| DRVr /TDF/XTC | 757 | 4.6 (4.0-5.3) |

73.2 (69.0-77.3) |

51.3 (46.7-55.8) |

83.0 (80.0-86.0) |

16.5 (13.2-19.9) |

| RAL/TDF/XTC | 588 | 3.5 (3.1-3.9) |

80.4 (76.7-84.2) |

60.7 (56.9-64.6) |

83.8 (79.9-87.8) |

11.7 (8.9-14.5) |

| ATVr/ABC/XTC | 330 | 1.9 (1.7-2.1) |

82.2 (77.8-86.6) |

69.7 (64.1-75.4) |

83.8 (79.8-87.9) |

16.6 (12.6-20.8) |

| EFV/ABC/XTC | 227 | 1.4 (1.2-1.6) |

90.4 (86.1-94.7) |

81.4 (76.0-86.8) |

91.1 (86.3-95.9) |

14.8 (10.0-19.5) |

| EVG/TDF/FTC | 20 | 0.2 (0.1-0.3) |

79.3 (61.3-97.3) |

56.6 (31.7-81.5) |

29.9 (4.9-54.8) |

n=4# |

| RPV/ TDF/XTC | 211 | 1.4 (1.0-1.7) |

77.5 (71.6-83.4) |

52.4 (45.1-59.6) |

72.8 (67.0-78.5) |

17.8 (13.0-22.7) |

| Alternative Initial Regimens | 1013 |

6.1 (5.6-6.6) |

77.3 (74.3-80.3) |

63.6 (59.6-67.6) |

83.0 (79.9-86.0) |

18.3 (15.5-21.1) |

| LPVr + TDF/XTC | 642 | 3.9 (3.5-4.3) |

78.3 (74.8-81.8) |

65.9 (61.1-70.7) |

84.0 (80.7-87.3) |

20.3 (16.6-24.0) |

| LPVr + ABC/XTC | 149 | 0.9 (0.7-1.1) |

72.9 (63.5-82.4) |

60.2 (50.4-70.0) |

82.4 (74.8-90.0) |

9.3 (4.3-14.4) |

| DRVr + ABC/XTC | 126 | 0.7 (0.6-0.8) |

72.1 (63.2-81.1) |

48.3 (38.8-57.8) |

78.4 (71.3-85.5) |

20.0 (9.9-30.1) |

| RAL + ABC/XTC | 96 | 0.5 (0.4-0.7) |

83.8 (72.9-94.7) |

72.6 (62.0-83.1) |

82.4 (74.7-90.0) |

17.0 (9.3-24.6) |

| NOT Recommended as Initial Regimens | 4796 |

29.0 (27.5-30.5) |

79.0 (77.4-80.7) |

67.4 (65.6-69.2) |

83.4 (82.1-84.8) |

16.8 (15.6-18.1) |

| Other regimens | 2291 |

13.4 (12.6-14.1) |

73.2 (70.7-75.7) |

58.8 (56.0-61.6) |

80.0 (78.0-82.0) |

16.9 (15.0-18.8) |

| Total | 16528 | 100 |

79.5 (78.3-80.7) |

65.5 (64.0-66.9) |

84.4 (83.5-85.4) |

15.7 (14.8-16.5) |

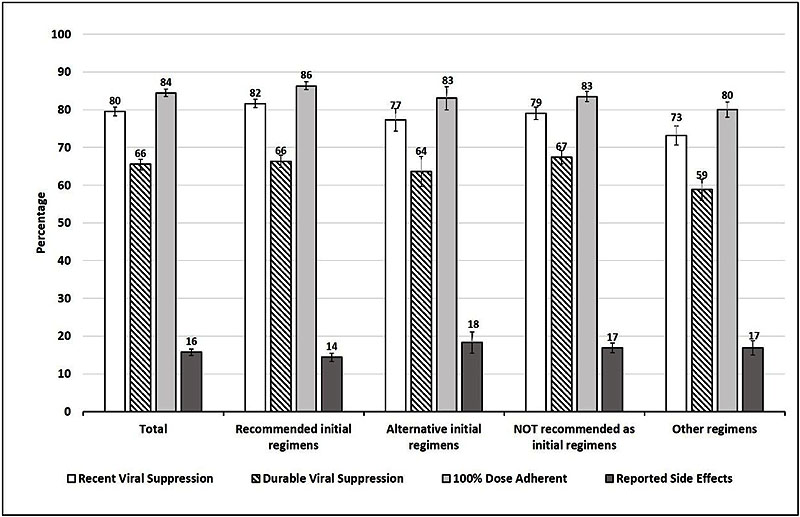

We assessed the association between ARV regimens with recent viral suppression, durable viral suppression, dose adherence, and self-reported side effects (Table 2, Fig. 1). Among participants prescribed preferred initial regimens, 81.6% achieved recent viral suppression, 66.3% achieved durable viral suppression, 86.3% reported fully dose-adherent in the 72 hours prior to interview, and 14.4% reported being troubled by ARV-related side effects in the 30 days prior to interview. For top 5 most frequently prescribed ARV regimens, EFV/TDF/XTC, ATVr/TDF/XTC, DRVr /TDF/XTC, LPVr/TDF/XTC, and RAL/TDF/XTC, persons prescribed EFV/TDF/XTC had the highest recent viral suppression (85.4%), durable viral suppression (72.6%), fully dose adherent (89.5%), and lowest in reporting side effects (14.1%). Among the recommended initial regimens, patients prescribed DRVr/TDF/XTC had the lowest recent viral suppression (73.2%), durable viral suppression (51.3%), and dose adherence (83.0%). Of all regimens, 1 in 5 (20%) of patients prescribed LPVr/TDF/XTC or DRVr/ABC/XTC reported experiencing side effects in the past 30 days.

Recent viral suppression is defined as the most recent viral load in the past 12 months prior to the interview as undetectable or <200 copies/ml. This information is based on data as recorded by medical record abstraction during the past 12 months prior to interview.

Durable viral suppression is defined as all plasma HIV viral load tests in the past year documented in the medical record as undetectable or <200 copies/ml.

ART adherent was defined as patients who self-report that they are currently taking ART and were 100% dose adherent in the past 3 days. A patient is defined as 100% adherent if they took their ART doses or set of pills/spoonfuls/injections of ART medications as prescribed by a health care provider in the last 3 days. Otherwise, they were considered as not adherent.

Reported side effects was defined as patients who self-reported that they were currently taking ART and were troubled by side effects from antiretroviral medications in the 30 days prior to the interview.

3.2. ART Initiation

Of persons prescribed ART, only 6.1% were initiated on ART in the past year; median time since ART initiation to interview date was 9.8 years (IQR: 3.9-15.4). About 6 out of 10 (6.1%) participants who reported that they initiated ART in the past year were more likely to be younger (<40 years), non-Hispanic black, at or below poverty level than those who initiated ART more than a year ago (Table 3). About half (47.1%) of this sample had stage 2 disease and half (47.3%) had AIDS (stage 3).

| - | Time of ART Initiation* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| - | ≤1 year Preceding Interview Date | >1 year Preceding Interview Date | p-value | ||

| Characteristic | na | % (CI)b | na | % (CI)b | |

| Total | 854 | 6.1 (5.6–6.7) | 13733 | 93.9 (93.3–94.4) | - |

| Age in years | <0.001 | ||||

| 18-29 | 210 | 24.4 (21.2–27.6) | 771 | 5.7 (5.0–6.3) | |

| 30-39 | 233 | 27.9 (24.9–30.9) | 2057 | 15.3 (14.5–16.1) | |

| 40-49 | 258 | 30.6 (26.6–34.7) | 4994 | 36.0 (35.1–37.0) | |

| ≥ 50 | 153 | 17.1 (14.4–19.7) | 5911 | 43.0 (42.0–44.0) | |

| Gender | 0.111 | ||||

| Male | 636 | 76.1 (72.6–79.6) | 10006 | 72.9 (70.7–75.2) | |

| Female | 202 | 22.3 (18.8–25.8) | 3542 | 25.7 (23.5–28.0) | |

| Transgender | 14 | 1.6 (0.6–2.6) | 183 | 1.3 (1.1–1.6) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | <0.001 | ||||

| Non-Hispanic black | 368 | 43.5 (35.8–51.3) | 5479 | 39.7 (33.2–46.2) | |

| Hispanic or Latinoc | 205 | 22.1 (18.1–26.2) | 2908 | 19.2 (15.0–23.4) | |

| Non-Hispanic white | 233 | 28.1 (22.3–34.0) | 4722 | 36.5 (31.1–41.8) | |

| Otherd | 48 | 6.2 (4.1–8.3) | 613 | 4.7 (4.0–5.4) | |

| Foreign Born | 0.178 | ||||

| Born in United States | 724 | 84.9 (81.7–88.2) | 11971 | 86.8 (85.3–88.2) | |

| Born outside United States | 130 | 15.1 (11.8–18.3) | 1758 | 13.2 (11.8–14.7) | |

| Education Attainment | 0.791 | ||||

| <High school | 166 | 18.9 (15.8–22.0) | 2783 | 19.5 (17.5–21.5) | |

| High school diploma or equivalent | 243 | 27.6 (23.9–31.4) | 3684 | 26.3 (24.7–27.9) | |

| >High school | 445 | 53.5 (48.7–58.2) | 7262 | 54.2 (50.9–57.4) | |

| Poverty levele in P12M | 0.041 | ||||

| Above poverty level | 423 | 50.8 (46.4–55.2) | 7446 | 55.9 (52.8–59.1) | |

| At or below poverty level | 396 | 45.3 (41.0–49.6) | 5907 | 41.2 (38.3–44.1) | |

| Unknown | 35 | 3.9 (2.6–5.2) | 380 | 2.9 (2.3–3.4) | |

| Homeless in P12M | 107 | 12.7 (10.5–14.8) | 1010 | 7.2 (6.5–7.9) | <0.001 |

| Incarcerated in P12M | 58 | 5.9 (4.2–7.7) | 611 | 4.6 (4.1–5.1) | 0.136 |

| Type of Health Insurance in P12M | <0.001 | ||||

| Any private insurance | 265 | 32.3 (25.6–39.0) | 4195 | 32.0 (28.8–35.1) | |

| Public insurance only | 312 | 32.5 (28.1–36.9) | 7149 | 49.8 (47.1–52.5) | |

| Ryan White program coverage only/Uninsured | 245 | 32.1 (25.8–38.4) | 2092 | 16.2 (13.7–18.6) | |

| Other coverage (unspecified) | 30 | 3.1 (1.3–5.0) | 271 | 2.1 (1.5–2.6) | |

| Any Non-injection Drug Use | 269 | 31.4 (27.4–35.5) | 3419 | 25.2 (23.8–26.6) | 0.001 |

| Any Injection Drug Use | 24 | 2.5 (1.4–3.6) | 322 | 2.2 (1.5–2.8) | 0.486 |

| Binge Drinker in Past 30 Days | 163 | 20.1 (17.2–23.0) | 2097 | 15.1 (14.4–15.8) | <0.001 |

| Current Smoker | 360 | 41.6 (37.5–45.7) | 5501 | 40.2 (38.5–41.8) | 0.454 |

| Had depression in past 2 weeks | 223 | 26.5 (23.1–30.0) | 2963 | 22.0 (20.8–23.3) | 0.007 |

| Clinical Indicators | - | ||||

| Time since HIV diagnosis (in years) | <0.001 | ||||

| ≤ 4 | 590 | 71.1 (67.4–74.7) | 2377 | 18.2 (17.2–19.2) | - |

| 5-9 | 140 | 16.3 (13.7–18.9) | 2990 | 21.7 (20.9–22.6) | |

| ≥ 10 | 124 | 12.6 (9.9–15.3) | 8366 | 60.0 (58.6–61.5) | |

| Stage of diseasef | <0.001 | ||||

| Stage 1 (HIV) | 44 | 5.6 (3.5–27.7) | 772 | 5.8 (5.3–6.4) | |

| Stage 2 (HIV) | 380 | 47.1 (43.6–50.7) | 2908 | 21.3 (20.3–22.2) | |

| Stage 3 (HIV and AIDS) | 427 | 47.3 (43.5–51.0) | 10028 | 72.9 (71.9–73.9) | |

| Geometric mean CD4 count (cells/µL) in P12M | <0.001 | ||||

| 0-199 | 189 | 21.9 (18.5–25.2) | 1552 | 11.4 (10.6–12.3) | |

| 200-349 | 195 | 23.2 (20.1–26.3) | 2272 | 16.9 (16.0–17.9) | |

| 350-499 | 234 | 29.1 (26.1–32.2) | 2945 | 22.5 (21.7–23.3) | |

| 500+ | 218 | 25.8 (22.0–29.6) | 6487 | 49.1 (47.9–50.4) | |

| Viral suppression: most recent viral load < 200 copies/mL or undetectable | 592 | 68.6 (65.1–72.2) | 11100 | 80.6 (79.4–81.9) | <0.001 |

| Durable viral suppression: all viral load in P12M < 200 copies/mL or undetectable | 132 | 14.7 (12.0–17.4) | 9503 | 68.8 (67.3–70.3) | <0.001 |

| Dose adherence in past 3 daysg | 690 | 83.7 (81.4–86.1) | 11348 | 85.0 (84.0–86.0) | 0.280 |

| Reported side effects from ART in past 30 daysg | 141 | 17.5 (14.2–20.8) | 2062 | 15.8 (14.9–16.8) | 0.338 |

| Survey year | 0.001 | ||||

| 2009 | 247 | 29.1 (24.0–34.3) | 3092 | 22.5 (20.6–24.5) | |

| 2010 | 229 | 26.2 (21.3–31.0) | 3341 | 23.8 (21.7–25.9) | |

| 2011 | 191 | 23.1 (18.8–27.3) | 3448 | 26.6 (24.5–28.6) | |

| 2012 | 187 | 21.6 (17.1–26.1) | 3852 | 27.1 (24.9–29.4) | |

Among persons that were prescribed ART and initiated ART in the past year, 80.5% were prescribed a recommended initial regimen, 4% an alternative initial regimen, 10% a not-recommended regimen, and 5.4% other regimens (Table 4). About half (45.7%) were prescribed the regimen combination of EFV/TDF/XTC. Persons prescribed EFV/TDF/XTC also had the highest dose adherence (88.8%). Among the recommended initial regimens, patients prescribed RAL/TDF/XTC had the highest recent viral suppression (80.6%).

| DHHS Guideline-Specified ARV Regimen as of December 2014 | n |

Prescribed ARV Regimen Col% (CI) |

Recent VL Suppressed Row% (CI) |

Dose Adherent Row% (CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recommended Initial Regimens | 680 | 80.5 (77.6-83.5) | 70.4 (66.9-74.0) | 85.4 (82.9-88.0) |

| EFV/TDF/XTC | 375 | 45.7 (41.7-49.6) | 71.2 (66.8-75.5) | 88.8 (85.5-92.0) |

| ATVr/TDF/XTC | 121 | 13.8 (11.4-16.3) | 67.7 (58.7-76.7) | 80.5 (73.1-87.9) |

| DRVr /TDF/XTC | 64 | 7.1 (5.4-8.9) | 66.5 (52.6-80.3) | 85.0 (76.4-93.6) |

| RAL/TDF/XTC | 57 | 6.3 (4.4-8.3) | 80.6 (69.0-92.2) | 85.2 (74.5-96.0) |

| EFV/ABC/XTC | 8# | |||

| ATVr/ABC/XTC | 6# | |||

| EVG/TDF/FTC | 4# | |||

| RPV/ TDF/XTC | 45 | 5.5 (3.3-7.8) | 60.2 (46.2-74.3) | 75.8 (63.4-88.2) |

| Alternative initial regimens | 31 | 4.0 (2.4-5.7) | 52.7 (34.1-71.3) | 62.1 (41.5-82.7) |

| DRVr + ABC/XTC | 4# | |||

| LPVr + ABC/XTC | 0 | |||

| LPVr + TDF/XTC | 23 | 3.2 (1.7-4.6) | ||

| RAL + ABC/XTC | 4# | |||

| NOT recommended as initial regimens | 93 | 10.0 (7.9-12.1) | 62.5 (49.2-75.7) | 78.8 (66.7-90.8) |

| Other regimens | 50 | 5.4 (3.9-6.9) | 65.0 (50.9-79.0) | 83.5 (72.8-94.2) |

| Total | 854 | 100 | 68.6 (65.1-72.2) | 83.7 (81.4-86.1) |

Our sensitivity analysis compared those who had an ART initiation date to those who did not have one. Patients who had missing initiation dates were older (>50 years), non- Hispanic black, had more than a high school education, lived at or below poverty level, experienced homelessness, and had been diagnosed more than 10 years ago compared to those who reported ART initiation dates (Supplemental Table 3).

4. DISCUSSION

In this large, geographically diverse, nationally representative sample of HIV-infected persons in care, 91.8% were prescribed ART with the percentage prescribed ART significantly higher in 2012 compared to 2009. Overall, persons prescribed ART regimens were more likely to be older and later in the course of their disease (e.g. longer history of diagnosed with HIV, more likely to have AIDS). Among persons prescribed ART, over half were prescribed a recommended initial regimen, while within those who initiated ART in the past year, over 80% were prescribed a recommended initial regimen. EFV/TDF/XTC was the most commonly prescribed regimen.

Although over 80% of persons who initiated ART in the past year were prescribed a recommended initial regimen, only 52% of all persons were prescribed a recommended initial regimen. Because ARV prescribing should be driven by clinician judgment and risk-benefit analysis of numerous ARV options, it is reassuring that relatively few persons were prescribed ARV regimens that have inferior efficacy or tolerability (e.g. ABC/3TC/ZDV, stavudine + others, nelfinavir + others) [1]. It is possible that most persons prescribed not-recommended regimens might be on second or third-line regimens that use second-line ARVs given limited treatment options due to resistance. In addition, this analysis highlights the reliance by providers on certain ARVs that are key components of most regimens (e.g. 72.5% of patients were on TDF; 66.0% on FTC; 44.5% on ritonavir). Some of these ARVs have known side effects (e.g. risk for renal dysfunction with TDF [20], drug-drug interactions with ritonavir [21]) and thus put a large percentage of the entire HIV-infected population at risk for developing these complications.

Although substantial data exist from randomized clinical trials on the efficacy and safety of particular ARV regimens, observational data from real-world clinical settings can be used to assess the real-world effectiveness and tolerability of ARV regimens, as persons who participate in clinical trials are often different than those in the general HIV-infected population (e.g. injection drug users, homeless persons, and racial and ethnic minorities are under-represented in clinical trials) [22-25]. Data from clinical trials suggest efficacy approaching 90% for most recommended regimens, but we found that overall only 79.5% achieved recent viral suppression and 65.5% achieved durable viral suppression. This gap between ARV regimen efficacy noted in clinical trials and real-world effectiveness is important for a few reasons. First, it helps informs national targets for achieving viral suppression and thus helps to estimate the expected drop-off between ART prescription and viral suppression at the population-level. For example, in this analysis, as in other U.S.-based studies [26-28], fewer than 90% of patients on ART achieved viral suppression, thus suggesting that international targets such as 90-90-90, which state that 90% of persons prescribed ART should achieve viral suppression, might be difficult to attain [29]. Second, as shown in this analysis and by others, certain sociodemographic (e.g. younger age, homeless), behavioral (e.g. injection drug use), and clinical (e.g. depression) factors were associated with decreased prevalence of viral suppression [30-36] and, as shown previously, persons with these characteristics are less likely to participate in HIV clinical trials [22-25]. Thus, population-level differences between all HIV-infected persons and those who participate in clinical trials might contribute to reduced real-world ART effectiveness compared to efficacy seen in clinical trials. A better understanding of the key factors associated with the gap between efficacy in clinical trials and real-world effectiveness could be used to design interventions to improve ART effectiveness.

Among top 5 most frequently prescribed ARV regimens, persons prescribed EFV/TDF/XTC were highest for recent viral suppression, durable viral suppression, fully dose adherent in past 72 hours, and lowest in reporting side effects. As newer recommended regimens are adopted in clinical practice (e.g. integrase strand transfer inhibitor-based regimens), additional analyses of population-level data on viral suppression and dose adherence should be conducted to confirm that benefits noted in clinical trials translate into real-world performance.

This study has a number of limitations. First, MMP is an annual, cross sectional survey and thus participants were not randomly allocated to regimen types. There may be possible survivor or selection bias among our patients, as the median time since ART initiation was nearly 10 years, and may have additional factors that contributed to virologic control and overall healthcare. Second, data on prior treatment history and ARV resistance were unavailable and thus, we could not restrict this analysis only to patients who were ARV naïve and did not have transmitted ARV resistance. As has been shown previously, patients on second and third line regimens are likely to have lower levels of viral suppression, lower adherence and more side effects [1, 37]. Moreover, we did not have information on all factors that might inform a clinician’s decision to prescribe an initial regimen, such as HLAB5701 testing or initial viral load. Third, ART initiation dates were self-reported and thus is subjected to recall bias if participants were diagnosed a long time ago. In our study, the majority (65%) of those with missing ART entry dates were those diagnosed more than 10 years ago. Fourth, dose adherence and side effect data were self-reported and were not collected using a systematic checklist such as might be done in a safety assessment in a clinical trial. In addition, symptom severity was not assessed. Fifth, DHHS guidelines change over time and thus some regimens that were recommended in 2009 (e.g. LPVr/ZDV/3TC) might no longer be on the recommended list in 2014. This is a major limitation in using this data to assess adherence to a single standard of care. However, our intention was to describe prescribing patterns and ART use rather than assessing adherence to a single set of guidelines. Moreover, this analysis includes data collected through May 2013 and thus does not include much information on newer ARV regimens, such as those containing elvitegravir or dolutegravir. Additionally, our study showed that ritonavir is the most commonly prescribed protease inhibitor (44%). In practice, ritonavir was mainly used as a pharmacokinetic enhancer and co-prescribed with other protease inhibitors such as atazanavir, lopinavir or darunavir, rather than a standalone ART. However, we do not have ritonavir dosing information in the current MMP dataset; thus our analysis cannot address this issue. Finally, our patient response rates ranged from 49% to 55%, although our use of population-based sampling methods and weighting adjustments for nonresponse should reduce bias [38], and the MMP population is demographically similar to all HIV-diagnosed persons in the United States [39]. Furthermore, our study participants are limited to HIV-positive persons who are known to be in medical care. We have no information about HIV-positive persons who are not in care or who have not been diagnosed with HIV. While important, the results of this analysis should be interpreted with caution when discussing all HIV-positive persons.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, over 90% of HIV-infected adults receiving medical care in the United States were prescribed ART. Of those prescribed ART, just over half were prescribed recommended initial regimens, which were found to be effective and tolerable. HIV providers should continue to prescribe ART according to established guidelines [1]. Given that new ARV regimens are being introduced, monitoring of ARV use at the population-level should be continued to provide ongoing assessments of ART effectiveness and tolerability in the United States.

FUNDING INFORMATION

Funding for the Medical Monitoring Project is provided by a cooperative agreement (PS09-937) from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

DISCLAIMER

The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

Not applicable.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

No Animals/Humans were used for studies that are base of this research.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank participating MMP patients, facilities, project areas, and Provider and Community Advisory Board members. We also acknowledge the contributions of the Clinical Outcomes Team and Behavioral and Clinical Surveillance Branch at CDC and the MMP 2009-2012 project areas. (http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/statistics/ systems/mmp/resources.html).