RESEARCH ARTICLE

Immunologic Restoration of People Living with Human Immunodeficiency Virus on Highly Active Anti-retroviral Therapy in Ethiopia: The Focus of Chronic Non-Communicable Disease Co-Morbidities

Tsegaye Melaku*, Girma Mamo, Legese Chelkeba, Tesfahun Chanie

Article Information

Identifiers and Pagination:

Year: 2019Volume: 13

First Page: 36

Last Page: 48

Publisher ID: TOAIDJ-13-36

DOI: 10.2174/1874613601913010036

Article History:

Received Date: 03/03/2019Revision Received Date: 11/04/2019

Acceptance Date: 25/04/2019

Electronic publication date: 31/05/2019

Collection year: 2019

open-access license: This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Public License (CC-BY 4.0), a copy of which is available at: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode. This license permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Background:

The life expectancy of people living with Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) has dramatically improved with the much-increased access to antiretroviral therapy. Consequently, a larger number of people living with HIV are living longer and facing the increased burden of non-communicable diseases. This study assessed the effect of chronic non-communicable disease(s) and co-morbidities on the immunologic restoration of HIV infected patients on highly active antiretroviral therapy.

Methods:

A nested case-control study was conducted among people living with HIV at Jimma University Medical Center from February 20 to August 20, 2016. Cases were HIV infected patients living with chronic non-communicable diseases and controls were people living with HIV only. Patient-specific data were collected using a structured data collection tool to identify relevant information. Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Science version 20.0. Logistic regressions were used to identify factors associated with outcome. Statistical significance was considered at p-value <0.05. A patient's written informed consent was obtained after explaining the purpose of the study.

Results:

A total of 240 participants (120 cases and 120 controls) were included in the analysis. Prevalence of hypertension was 12.50%, and diabetes was 10.84%. About 10.42% of study participants were living with multi-morbidity. At baseline, the mean (±SD) age of cases was 42.32±10.69 years, whereas it was 38.41±8.23 years among controls. The median baseline CD4+ cell count was 184.50 cells/µL (IQR: 98.50 - 284.00 cells/µL) for cases and 177.0 cells/µL (IQR: 103.75 - 257.25 cells/µL) for controls. Post-6-months of highly active antiretroviral therapy initiation, about 29.17% of cases and 16.67% of controls had poor immunologic restoration. An average increase of CD4+ cell count was 6.4cells/µL per month among cases and 7.6 cells/µL per month among controls. Male sex [AOR, 3.51; 95% CI, 1.496 to 8.24; p=0.004], smoking history [AOR, 2.81; 95% CI, 1.072, to 7.342; p=0.036] and co-morbidity with chronic non-communicable disease(s) [AOR, 3.99; 95% CI, 1.604 to 9.916; p=0.003)] were independent predictors of poor immunologic restoration.

Conclusions:

Chronic non-communicable disease(s) have negative effects on the kinetics of CD4+ cell count among HIV-infected patients who initiated antiretroviral therapy. So the integration of chronic non-communicable disease-HIV collaborative activities will strengthen battle to control the double burden of chronic illnesses.

1. INTRODUCTION

Human Immune Deficiency Virus (HIV) infection is a global pandemic, with cases reported from virtually every country According to the World Health Organization (WHO) and United Nations program on HIV and acquired immune deficiency syndrome (UNAIDS) report, by the end of 2015, about 36.7 million individuals were living with HIV globally and more than 95% of them reside in developing countries. There are an estimated 26.6 million people living with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa, which is nearly 73% of the global total. Ten countries of Africa, including Ethiopia, account for 81% of all people living with HIV in the region [1]. In Ethiopia, a single point HIV related estimates and projections in 2014 show a national HIV prevalence of 1.14%. From this, approximately 769,500 Ethiopians are currently living with HIV [2].

|

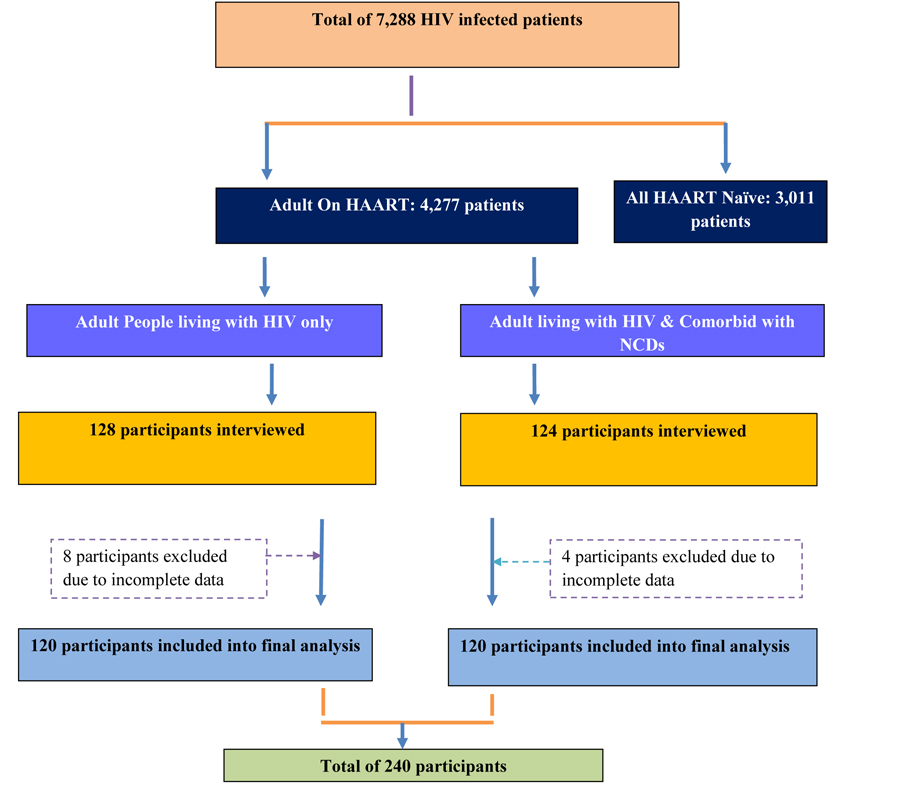

Flowchart. Participants selection flow chart. |

Likewise, Non-communicable Diseases (NCDs) also kill more than 36 million people each year globally. Majority of these deaths occur in low and middle-income countries. More than 25% of all NCD deaths occur before the age of 60 years. Ninety percent of these premature deaths occur in low and middle-income countries [3]. According to the WHO’s report, in Ethiopia, the probability of dying between ages 30 and 70 years from the 4 main NCDs (i.e. cancers, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and chronic pulmonary diseases) reaches 15% [4]. Low-and-middle income countries, which already have a high magnitude of HIV are expected to share a high burden of NCD co-morbidity due to the associated increase in the incidence of NCDs [4]. Though HIV disease has one necessary cause, which is HIV virus, many chronic NCDs, including heart disease, cancer, and chronic pulmonary disease result from the interaction of multiple risk factors, such as smoking, nutrition, physical activity, and genetics. For example, the prevalence of smoking is considerably higher in people with HIV than in the general population [5].

The global success in bringing antiretroviral treatment to HIV-infected patients in the developing world has brought a new set of health challenges. Many patients once condemned to death by Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS), now suffer from NCDs related to the infection itself, the drugs used to treat it, or the simple process of aging [6]. With the widespread introduction of highly effective combination ART for HIV infection, HIV-associated morbidity and mortality has dramatically decreased [5]. Despite marked increases in life expectancy, still, mortality rates among HIV-infected persons remain 3-15 times higher than those seen in the general population [7]. Although some of the excess mortality observed among HIV-infected persons can be directly attributed to illnesses that occur as a consequence of immunodeficiency, more than half of the deaths observed in recent years among ART-experienced HIV infected patients are attributable to Non-infectious Comorbidities (NICMs). These include cardiovascular disease (CVD), hypertension, cancers, and bone fractures, renal failure, and Diabetes Mellitus (DM). These diseases often coexist and are associated with advancing age in the general population [8]. Therefore, the objective of this study was to assess the effect of chronic non-communicable disease(s) co-morbidities on the immunologic outcome of HIV infected patients on highly active antiretroviral therapy.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Study Design and Setting

A hospital based nested case-control study design was conducted from February 20 to August 20, 2016, at ART clinic of Jimma University Medical Center (JUMC) among adult (≥18 years old) HIV infected patients on HAART who fulfilled the inclusion criteria. JUMC is the only teaching and referral hospital in the South-Western part of Ethiopia with a bed capacity of 600. Geographically, it is located in Jimma town 352 km South-West of Addis Ababa, the capital. It provides services for approximately 9000 inpatient and 80,000 outpatient clients per year with a catchment population of about 15 million people.

2.2. Study Population

From all known HIV infected patients (both on HAART and HAART naïve) on follow-up at ART clinic of Jimma University Medical Center, adult people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) on HAART, who were diagnosed to have one or more chronic NCD(s) were taken as cases and who were not diagnosed to have any type of chronic NCD(s) were considered as controls.

2.3. Participants Inclusion and Selection Procedures

At the study area, the number of people living with HIV/AIDS and diagnosed with NCDs were unknown and had a separate follow-up clinic and day of consultation. Thus, all patients living with HIV/AIDS, who were coming for HAART refill and consultation during the data collection period, were interviewed and their medical record (of HIV and NCD) reviewed. Then, the patient-reported NCD diagnosis was checked for information genuineness through their respective follow-up clinic with the help of the patient. And finally, 120 HIV infected patients living with NCD were included in the study. Control group inclusion was done in parallel with the number of cases per day, i.e. if 2 patients in case group were interviewed per day, the same rule was followed for the control group. Accordingly, 120 patients from the case group and 120 patients from the control group were included in the final analysis.

2.4. Data Collection Tool and Procedure

A structured data collection questionnaire was developed by researchers from different relevant literatures. For assessing information related to NCD, questionnaires developed by World Health Organization (WHO) on a stepwise approach to chronic disease risk factor surveillance [9, 10] in developing countries was used with modifications according to the study objective. Two trained data collectors (both ART trained nurses) interviewed the study participant’s and reviewed patient charts and medical records for the respective information after all data collection tools were pre-tested.

2.5. Data Processing and Analysis

Data were entered into the computer using EpiData version 3.1 and exported to the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 20.0 for analysis. Differences between mean values were evaluated using Student's t-test while proportions were compared using the Pearson's Chi-square test. Multivariable logistic regression analyses were used to assess the crude and adjusted effect of seemingly significant predictors of immunologic outcome. Variables that had p-value≤ 0.25 on univariate analysis were eligible for multivariate logistic regression. Categorical and continuous data were expressed as percentages and mean ± standard deviation, respectively. Descriptive statistics were applied for the analysis of patient characteristics, including means, Standard Deviations (SD), medians, and percentiles and categorical variables were analyzed by using the chi-square test. A p-value of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

2.6. Outcome Measures

Although the WHO recommends three types of criteria to define antiretroviral treatment failure, (i.e. Clinical, immunological, and virologic), the focus of this study was on immunological failure, which is defined as an increase of CD4+ cell count < 50cells/µL at 6 months; or < 100cells/µL at 12-24 months [11, 12]. In this study, the least recommended increase in CD4+ cell count, which is 50 cells/µL post-6 months of HAART were considered. If the increase in CD4+ cell count from baseline is less than 50 cells/µL, it was quoted as ‘’poor immunologic restoration.”

3. ETHICAL APPROVAL

Ethical clearance & approval was obtained from the InStitutional Review Board (IRB) of Jimma University. The data that were collected from the JUMC ART clinic was preceded by a formal request letter from Jimma University. Written informed consent was taken from each study participant after a clear orientation of the study objective. The raw data were not made available to anyone and not used as the determinant of the participant. Strict confidentiality was assured through anonymous recording and coding of questionnaires and placing them at a safe place. The patient had full right not to participate and as well as leave the study at any time.

4. DEFINITION AND EXPLANATION OF TERMS

4.1. Good Immunologic Restoration

Increase in CD4+ cell count at least by 50cells/µL from baseline after 6 months of HAART initiation [11, 12].

4.2. Poor Immunologic Restoration

Increase in CD4+ cell count by less than 50cells/µL from baseline after 6 months or fall of follow-up CD4+cell count from baseline after 6 months of HAART initiation [11, 12].

4.3. Co-Morbidity

Diseases or disorders that exist together with an index disease or co-occurrence of two or more diseases or disorders in an individual.

4.4. Chronic Non-Communicable Disease

Diseases which cannot be transmitted to other through contact from the index person and not caused by disease-causing microorganisms, and patients are on follow-up for care and treatment at health institution at least for the last 30 days.

4.5. Multi-Morbidity

Living with two or more types of chronic non-communicable diseases.

4.6. Case

People living with HIV/AIDS on HAART and were diagnosed to have one or more NCD(s) based on patient self-report and diagnostic and using medication(s) as a proxy indicator for chronic disease diagnosis within the past 30 days.

4.7. Control

People living with HIV/AIDS on HAART and were not diagnosed to have any type of NCD(s) within the past 30 days.

5. RESULTS

5.1. Baseline Characteristics of the Study Population

A total of 240 (99 male and 141 female) participants included in the study (120 cases & 120 controls). The mean (±SD) age among cases was 42.32±10.69 years, whereas it was 38.41±8.23 years among controls. More proportions of patients in both groups were in the age range of 35-50 (41.67% of cases and 47.50% of controls). Regarding body weight, about 32.08% of participants were above the ranges of recommended Body Mass Index (BMI) (i.e.>25kg/m2). About 18.33% cases and 16.67% of controls were below a BMI of 18kg/m2. About 45% of the study participants were married and 62.08% were living with immediate family. Most of them attended formal education and 15.83% had no formal education (Table 1).

| Variables | Case [n (%)] | Control [n (%)] | Total [n (%)] | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 52 (43.33) | 47 (39.17) | 99 (41.25) | 0.256 |

| Female | 68 (56.67) | 73 (60.83) | 141 (58.75) | ||

| Age | Mean ±SD | 42.32±10.69 | 38.41±8.23 | 0.154 | |

| 18 – 35 | 39 (32.50) | 43(35.83) | 82(34.17) | ||

| 35- 50 | 50(41.67) | 57 (47.50) | 107(44.58) | ||

| ≥ 50 | 31(25.83) | 20 (16.67) | 51 (21.25) | ||

| Baseline weight (Kg) (Mean ±SD) | 56.36±10.94 | 53.42 ±7.87 | 0.053 | ||

| Current weight (Kg) (Mean ±SD) | 58.92±11.69 | 55.62±8.34 | 0.042 | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | Mean ±SD | 22.29±4.04 | 21.03 ±3.04 | 0.028 | |

| <18 | 22 (18.33) | 20 (16.67) | 42 (17.50) | ||

| 18 -24.9 | 62(51.67) | 83 (69.17) | 145 (60.42) | ||

| 25-29.9 | 22(18.33) | 17 (14.16) | 39(16.25) | ||

| ≥30 | 14(11.67) | - | 14(5.83) | ||

| Marital status | Single | 20(16.67) | 16 (13.33) | 36 (30) | 0.323 |

| Married | 50(41.67) | 58 (48.34) | 108 (45) | ||

| Divorced | 26 (21.66) | 28 (23.33) | 54 (22.50) | ||

| Widowed | 24(20) | 18 (15) | 42 (17.50) | ||

| Educational status | Had no formal education | 21(17.5) | 17 (14.17) | 38 (15.83) | 0.054 |

| Primary | 48(40) | 64 (53.33) | 112(46.67) | ||

| Secondary | 31(25.83) | 20 (16.67) | 51(21.25) | ||

| College and above | 20 (16.67) | 19 (15.83) | 39 (16.25) | ||

| Residence | Rural | 35 (29.17) | 36 (30) | 71 (29.58) | 0.500 |

| Urban | 85 (70.83) | 84 (70) | 169(70.42) | ||

| Monthly income(ETB) | No regular income | 49(40.83) | 45 (37.50) | 94 (39.17) | 0.181 |

| <1000 | 12(10) | 21 (17.5) | 33(13.75) | ||

| 1000- 2000 | 26 (21.67) | 21 (17.5) | 47 (19.58) | ||

| 2000-3000 | 15 (12.50) | 17 (14.17) | 32(13.33) | ||

| ≥3000 | 18 (15) | 16 (13.33) | 34 (14.17) | ||

| Living status | Living with immediate family | 74 (75) | 75 (77.5) | 149 (62.08) | 0.732 |

| Living with extended family | 28(18.8) | 26 (16.2) | 54 (22.50) | ||

| Living alone | 18 (6.2) | 17 (5) | 35(14.58) | ||

| Other* | - | 2 (1.2) | 2 (0.84) | ||

| Occupation | Govt employee | 30 (25) | 28 (23.33) | 58(24.17) | 0.528 |

| Non-govt employee | 18(15) | 16 (13.33) | 34 (14.17) | ||

| Self-employed | 31 (25.83) | 40 (33.34) | 71(29.58) | ||

| Unemployed | 41(34.17) | 36 (30) | 77 (32.08) | ||

| Behavioral Measure | Smoker | 35(29.17) | 31(25.83) | 66 (27.5) | 0.260 |

| Alcoholic | 58 (48.33) | 66 (55) | 124(51.67) | 0.134 | |

| Chat Chewer | 34 (28.33) | 35 (29.17) | 69 (28.75) | 0.500 | |

| Herbal/traditional medicine user | 25 (20.83) | 25 (20.83) | 50 (20.83) | 0.627 | |

About 62.5% of patients among case and 58.33% among control were on cotrimoxazole preventive therapy and 42.5% of cases and 38.33% of controls took isoniazid (INH) preventive therapy. There was no difference with regard to tuberculosis (TB) treatment history among the groups (p=0.433). The most common type of TB among study participants was pulmonary TB, accounting for 42.57%. The median baseline CD4+ cell count was 184.50 cells/µL) [Interquartile range (IQR): 98.50 - 284.00 cells/µL)] for case group and 177.0 cells/µL) [IQR: 103.75 - 257.25 cells/µL] for control group. The median baseline CD4+ count wasn’t significantly different between the two groups (Mann-Whitney U-test, p=0.564). At baseline 75 (62.5%) of cases and 67 (55.83%) of controls were in advanced WHO clinical stage (III and IV). Median follow up duration was 76.50 months [IQR: 55.00 - 99.75months] for controls. Similarly, cases had a median follow up duration of 73 months [IQR: 56.00 - 107.75 months]. This was a comparable follow up duration (Mann-Whitney U-test, p=0.604) among the groups (Table 2).

| Variables | Case n (%) | Control n (%) | Total n (%) | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTX prophylaxis | Yes | 75 (62.5) | 70 (58.33) | 145(60.42) | 0.253 |

| No | 45 (37.5) | 50 (41.67) | 95 (39.58) | ||

| INH prophylaxis | Yes | 51 (42.5) | 46 (38.33) | 97 (40.42) | 0.255 |

| No | 69 (57.5) | 74 (61.67) | 143(59.58) | ||

| TB treatment history | Yes | 73(60.83) | 75 (62.5) | 148(61.67) | 0.433 |

| No | 47 (39.17) | 45 (37.5) | 92(38.33) | ||

| Type of TB | Pulmonary | 34 (46.57) | 29 (38.67) | 63 (42.57) | 0.426 |

| Disseminated | 21(28.76) | 22 (29.33) | 43 (29.06) | ||

| Unknown | 18 (24.65) | 24 (32) | 42(28.37) | ||

| Clinical stage(WHO) | Stage I | 15 (12.5) | 18 (15) | 33(13.76) | 0.018 |

| Stage II | 30(25) | 35 (29.17) | 65 (27.08) | ||

| Stage III | 44 (36.67) | 48 (40) | 92 (38.33) | ||

| Stage IV | 31 (25.83) | 19 (15.83) | 50 (20.83) | ||

| Eligibility reason | CD4+ count | 36 (30) | 47 (39.17) | 83 (34.58) | 0.039 |

| Clinical | 27 (22.5) | 18 (15) | 45 (18.75) | ||

| CD4+ count & clinical | 57 (47.5) | 55 (45.83) | 112 (46.67) | ||

| Baseline CD4+ count (cells/µL) | Median | 184.50 | 177 | 182.00 | 0.564 |

| <200 | 59 (49.17) | 58 (48.33) | 117 (48.75) | ||

| 200 −349 | 33 (27.5) | 36 (30) | 69 (28.75) | ||

| 350 − 499 | 15 (12.5) | 15 (12.5) | 30 (12.5) | ||

| ≥500 | 13(10.83) | 11 (9.17) | 24 (10) | ||

| Time elapsed till HAART initiation (in months) | Within the same month | 51(42.5) | 39 (32.5) | 90 (37.5) | 0.038 |

| 1-24 | 45(37.5) | 45 (37.5) | 90 37.5 | ||

| ≥24 | 24 (20) | 36 (30) | 60(25) | ||

| Median duration on HAART (in months) | 73 | 76.50 | 0.604 | ||

| Median duration with HIV (in months) | 80 | 94.50 | 0.140 | ||

| Functional Status | Working | 90 (75) | 93 (77.5) | 183(76.25) | 0.305 |

| Ambulatory | 30 (25) | 27 (22.5 | 57 (23.75) | ||

| Regimen Change | Yes | 68 (56.67) | 72 (60) | 140(58.33) | 0.32 |

| No | 52 (43.33) | 48 (40) | 100 (41.67) | ||

Currently, about 92 (76.67%) of >the cases and 90(75%) of controls was on first line HAART regimens (Table 3). With regard to non-communicable disease(s) (NCD(s)), their prevalence among HIV infected patients were: hypertension accounts 12.50%, followed by diabetes (10.84%). About 10.42% of study populations were diagnosed with multi-morbidity, i.e. living with two and/or more NCD(s) (Table 4).

| Regimens | Case n (%) | Control n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| AZT + 3TC + NVP | 26(21.66) | 25(20.84) |

| AZT + 3TC + EFV | 11(9.17) | 21 (17.50) |

| TDF + 3TC + EFV | 41(34.16) | 33(36.26) |

| TDF + 3TC + NVP | 14(11.676) | 11(27.50) |

| TDF + 3TC + ATV/r | 5 (4.17) | 10(8.34) |

| ABC + DDI + LPV/r | 5 (4.17) | 6(5) |

| ABC + DDI + EFV | 5 (4.17) | 6(5) |

| AZT + 3TC + ATV/r | 8 (6.67) | 4 (3.33) |

| ABC + 3TC + ATV/r | 5(4.17) | 4(3.33) |

Measurements of adherence level were done depending on 8-items modified Morisky's adherence scale (MMAS-8). Low adherence was considered if MMAS-8 < 6, medium adherence if MMAS-8 is between 6 to <8 and high adherence if MMAS-8 equals to 8. Accordingly, about 52.50% of the case group had high adherence, which was relatively low as compared to the control group (62.50%). Low adherence was 41.20% and 28.80% for cases and controls respectively Fig. (1).

| Types of NCD | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Diabetes | 26 | 10.84 |

| Cardiac (Heart failure) | 12 | 5.00 |

| Hypertension | 30 | 12.50 |

| Asthma/COPD* | 11 | 4.58 |

| Mental Illness | 8 | 3.33 |

| Epilepsy | 8 | 3.33 |

| Multi-morbidity** | 25 | 10.42 |

5.2. Immunologic Response of Study Participants

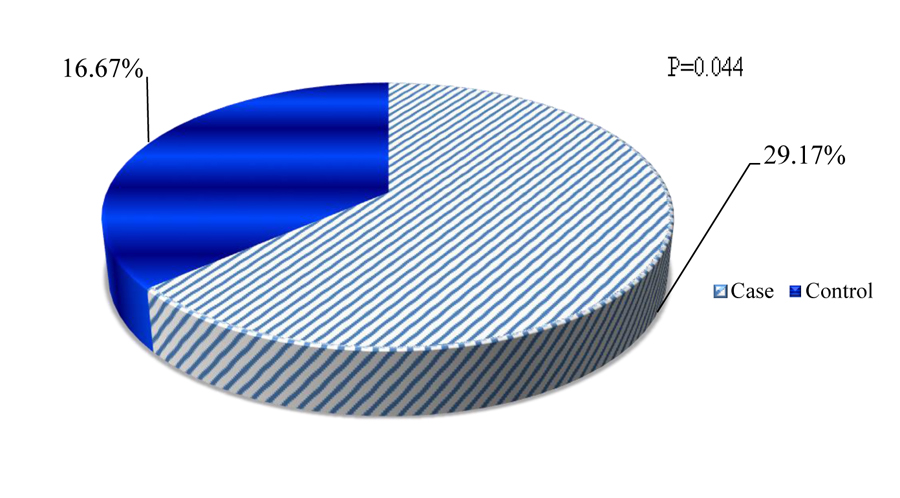

Quantitative restoration of CD4+ cells is one of the principal pieces of evidence for immune recovery during HAART initiation. Depending on the minimum recommended CD4+ cells restoration criteria (post-6 months of HAART initiation), poor immunologic restoration was seen among 35(29.17%) cases and it was 20(16.67%) among controls (Fig. 2).

|

Fig. (1). Proportions of study participants depending on adherence level. |

|

Fig. (2). Proportions of poor immunologic restoration post-6 months of HAART initiation. |

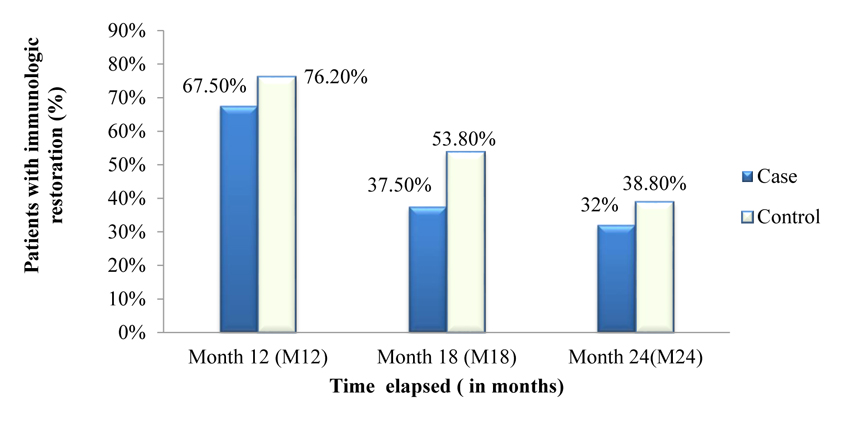

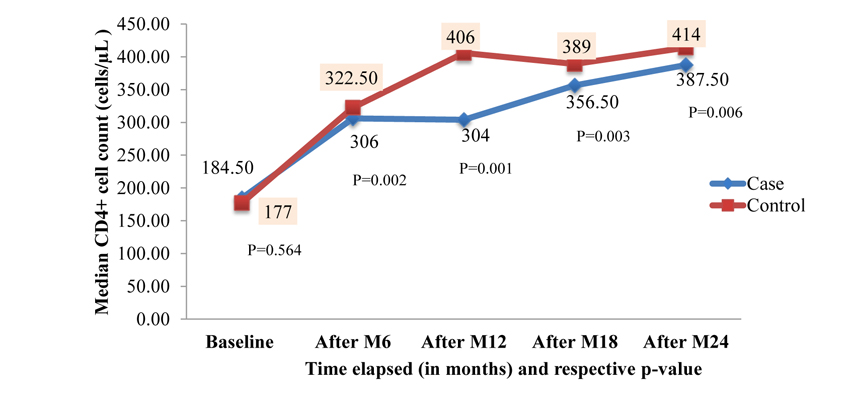

Figs. (3 and 4) depicts the trends of immunologic response to HAART over 24 months after ART initiation among case and control. Accordingly, about 67.50%, 37.50% and 32% of cases showed a good response to HAART (i.e. at least incre- ment of CD4+ cells count by 50cells/µL in each interval of months) at 6 months, 12 months and 18 months respectively. There was an overall slight increase in CD4+ cell count over the two years with an average increase of 6.4 cells/µL per month in the case of a group and 7.6 cells/µL per month in control group.

|

Fig. (3). A 2 years trends in immunologic response of study participants. |

|

Fig. (4). Median CD4+ cell count changes of study participants over 2 years. |

5.3. Socio-Demographic and Behavioral Factors Affecting Immunologic restoration

On the univariate analysis, sex was significantly associated with poor immunological restoration. The odds of poor immunological restoration >were3.69 times more likely among males than females [Crude Odds Ratio (COR), 3.69; 95%CI, 1.71 to 8.00; p=0.001]. The adjusted analysis also remained in the same direction [AOR, 3.51; 95%CI, 1.496 to 8.241; p=0.004], indicating that male sex was the independent predictor of poor immunological restoration. Occupational status of the patients was assessed for its relation with poor immunological restoration and found that unemployed [COR, 3.42, 95%CI, 0.618 to 6.037; p=0.257] and self-employed [COR, 1.37; 95%CI, 0.812 to 7.683; p=0.110] participants were found to have higher odds of experiencing poor immunological restoration. Another potential predictor for poor immunologic response was Body Mass Index (BMI). On univariate analysis, BMI less than 18kg/m2 was significantly associated with poor immunologic response [COR, 2.62; 95% CI, 1.026 to 6.686; p=0.044]. Similarly, on multivariate analysis, odds of poor immunologic response was 2.41 times more likely [95%CI, 0.904 to 6.400; p=0.079] among the BMI <18kg/m2 when compared with participants with BMI ≥18kg/m2 (Table 5).

| Variables | Immunologic Restoration | P-Value | COR (95% CI) | P-Value | AOR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good | Poor | ||||||

| Age (years) | 18-35 | 67 | 15 | 1.000 | - | 1.000 | - |

| 35-50 | 82 | 25 | 0.166 | 1.90 (.766, 4.716) | 0.603 | 1.30 (0.481,3.521) | |

| >50 | 36 | 15 | 0.031 | 3.38 (1.12, 10.22) | 0.095 | 3.06 (0.822,11.41) | |

| Gender | Female | 118 | 23 | 1.000 | - | 1.000 | - |

| Male | 67 | 32 | 0.001 | 3.69 (1.71, 8.00) | 0.004 | 3.51 (1.496,8.241) | |

| Marital Status | Single | 30 | 6 | 1.000 | - | 1.00 | - |

| Married | 79 | 29 | 0.103 | 0.563(0.704, 44.93) | 0.124 | 0.641 (0.106–3.872) | |

| Divorced | 42 | 12 | 0.224 | 0.389(0.436, 34.68) | 0.519 | 0.473 (0.326–0.687) | |

| Widowed | 34 | 8 | 0.304 | 0.333 (0.34, 33.11) | 0.625 | 0.473 (0.326–0.687) | |

| Educational Status | Had no formal education | 30 | 8 | 1.000 | - | - | - |

| Primary school | 87 | 25 | 0.630 | 1.39 (0.366, 5.277) | - | - | |

| Secondary school | 38 | 13 | 0.463 | 1.74 (0.397, 7.623) | - | - | |

| College & above | 30 | 9 | 0.479 | 1.79 (.358, 8.898) | - | - | |

| Occupation | Gov’t employee | 48 | 10 | 1.000 | - | 1.000 | - |

| NGO employee | 25 | 9 | 0.25 | 0.52 (0.166, 1.618) | 0.219 | 0.36(0.072,1.830) | |

| Self -employed | 52 | 19 | 0.110 | 1.37 (0.812, 7.683) | 0.964 | 0.96 (0.186,4.999) | |

| Unemployed | 60 | 17 | 0.257 | 3.42(0.618, 6.037) | 0.454 | 3.38(0.140, 81.560) | |

| Monthly Income (ETB) | No regular income | 72 | 22 | 1.000 | - | - | - |

| <1000 | 26 | 7 | 0.626 | 0.71 (0.185, 2.765 | - | - | |

| 1000- 2000 | 34 | 13 | 0.517 | 1.36 (0.534, 3.482) | - | - | |

| 2000- 3000 | 25 | 7 | 0.706 | 0.77 (0.197, 3.001) | - | - | |

| ≥3000 | 28 | 6 | 0.555 | 0.67 (0.173, 2.564) | - | - | |

| Residence | Rural | 54 | 17 | 1.000 | - | - | - |

| Urban | 131 | 38 | 0.990 | 0.99(0.389, 2.540) | - | - | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | <18 | 23 | 19 | 0.044 | 2.62(1.026,6.686) | 0.079 | 2.41 (0.904,6.400) |

| ≥ 18 | 162 | 36 | 1.000 | - | 1.000 | - | |

| Smoking history | Yes | 46 | 20 | 0.037 | 2.60 (1.057,6.377) | 0.036 | 2.81 (1.072,7.342) |

| No | 139 | 35 | 1.000 | - | 1.000 | - | |

| Alcohol history | Yes | 91 | 33 | 0.123 | 1.83(.850,3.930) | 0.077 | 2.10(0.924,4.734) |

| No | 94 | 32 | 1.000 | - | 1.000 | - | |

| Chat chewing | Yes | 50 | 19 | 0.228 | 0.58 (0.236, 1.410) | 0.216 | 1.83(0.704,4.741) |

| No | 135 | 36 | 1.000 | - | 1.000 | - | |

| Current CPT use | Yes | 105 | 40 | 1.000 | - | 1.000 | - |

| No | 80 | 15 | 0.014 | 0.27 (1.266, 8.426) | 0.019 | 0.31(0.118,.8270) | |

| TB history | Yes | 119 | 29 | 0.035 | 2.28 (1.062, 4.876) | 0.091 | 1.51 (0.229,1.116) |

| No | 66 | 26 | 1.000 | - | 1.000 | - | |

| Types of TB | Pulmonary | 48 | 15 | 1.000 | - | - | - |

| Disseminated | 34 | 9 | 0.467 | 0.59(0.144, 2.434) | - | - | |

| Unknown | 28 | 14 | 0.271 | 1.86 (0.615, 5.646) | - | - | |

| Current IPT use | Yes | 75 | 22 | 0.744 | 0.88 (0.401, 1.922) | - | - |

| No | 110 | 33 | 1.000 | - | - | - | |

| Regimen change | Yes | 115 | 25 | 0.004 | 0. 33(0.153, 0.703) | 0.113 | 0.41(0.134,1.237) |

| No | 70 | 30 | 1.000 | - | 1.000 | - | |

| WHO clinical stage | I +II | 77 | 21 | 1.000 | - | - | - |

| III +IV | 108 | 34 | 0.311 | 1.53 (.673,3.458) | - | - | |

| Adherence | High adherence | 55 | 21 | 1.000 | - | - | - |

| Medium adherence | 59 | 13 | 0.843 | 1.09(0.486,2.420) | - | - | |

| Low adherence | 71 | 21 | 0.787 | 1.22 (0.285,5.232) | - | - | |

| Time elapsed till HAART initiation(in months) | Within the same month | 70 | 20 | 1.000 | - | 1.000 | - |

| 1 to 24 | 74 | 16 | 0.698 | 0.69(0.281,1.735) | 0.442 | 0.673 (0.245,1.848) | |

| ≥ 24 | 41 | 19 | 0.072 | 2.33(0.927,5.874) | 0.312 | 1.99 (0.523,7.625) | |

| Duration with HIV (in months) | 6 to 24 | 20 | 7 | 1.000 | - | - | - |

| 24 to 60 | 31 | 11 | 0.5211 | 1.86(0.280,12.31) | - | - | |

| 60 to 120 | 93 | 26 | 0.605 | 1.39(0.397,4.889) | - | - | |

| ≥ 120 | 41 | 11 | 1.000 | 1.02(0.381,2.621) | - | - | |

| Duration on HAART(in months) | 6 to 24 | 24 | 12 | 1.000 | - | 1.000 | - |

| 24 to 60 | 40 | 15 | 0.220 | 1.02 (0.131,1.598) | 0.272 | 1.002 (0.095,1.938) | |

| 60 to 120 | 95 | 22 | 0.019 | 2.57 (0.083,0 .801) | 0.097 | 2.78 (0.061,1.262) | |

| ≥ 120 | 26 | 6 | 0.052 | 1.04 (0.011,1.020) | 0.160 | 1.53 (0.011,2.095) | |

| NVP based regimen | Yes | 56 | 20 | 0.373 | 0.69 (0.314,1.544) | - | - |

| No | 129 | 35 | 1.000 | - | - | - | |

| EFV based regimen | Yes | 91 | 15 | 0.259 | 1.56 (0.723,3.345) | - | - |

| No | 94 | 40 | 1.000 | - | - | ||

| PI-based regimen | Yes | 27 | 20 | 0.127 | 1.07(0.087,1.432) | - | - |

| No | 158 | 35 | 1.000 | - | - | - | |

| Baseline CD4+ (cells/ µL) | <200 | 91 | 26 | 0.026 | 2.36(1.108,5.006) | 0.060 | 1.41 (0.159,1.038) |

| ≥200 | 94 | 29 | 1.000 | 1.000 | - | ||

| NCD co-morbidity | Yes | 79 | 41 | 0.061 | 2.08(0.966,4.475) | 0.003 | 3.99(1.604,9.916) |

| No | 106 | 14 | 1.000 | - | 1.000 | - | |

5.4. Clinical Factors Affecting the Immunologic Outcome

Both univariate and multivariate analyses were carried out to assess clinical factors associated with poor immunological restoration. On univariate analysis, baseline CD4+ cell >count was significantly associated with poor immunological restoration. The odds of poor immunological restoration was more than two times among patients with CD4+ cell count below 200 cells/ µL[COR, 2.36; 95%CI, 1.108 to 5.006; p=0.026]. The univariate analysis being on HAART for the long duration of >time was significantlyassociated with poor immunologic restoration [(COR 2.57; 95%CI, 0.083 to 0.801; p=0.019), (COR, 1.04; 95%CI, 0.011 to 1.020; p=0.052)] at 5 to 10 years and greater than 10 years respectively. However, though odds of treatment failure >are still highas compared to those people taking HAART for a short period of time, on multivariate analysis, it was not statistically significant.

The baseline WHO clinical stage was also assessed as potential predictor >and it wasfound that those patients in WHO clinical stage III and IV [Adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR) 1.322; 95%CI, 0.422 to 4.140; p=0.632] were found to have higher odds of experiencing poor immunologic restoration, but this was not statistically significant. TB treatment history [COR, 2.28; 95%CI, 1.062 to 4.876], living long duration with HIV, for example, greater than 5 years [COR, 1.39; 95%CI, 0.397 to 4.889)], increased the likelihood of poor immunologic restoration on univariate and multivariate analysis. On multivariate analysis, time elapsed till HAART initiation, specifically greater than 2 years increased the likelihood of poor immunologic restoration [AOR, 1.99; 95% CI, 0.523 to 7.625]. Additionally, on univariable analysis, the effect of NCD comorbidities among the study participants showed that the odds of poor CD 4+ cell restoration is twice as high as compared to patients with no NCD co-morbidities [COR,2.08; 95%CI, 0.966 to 4.475; p=0.061). But, after fit to multivariable logistic regression NCD–co-morbidity became the independent predictor for poor immunologic restoration [AOR, 3.99; 95%CI, 1.604 to9.916; p=0.003]. By and large, male sex [AOR, 3.51; 95% CI, 1.496 to 8.24; p=0.004], smoking history [AOR, 2.81; 95% CI 1.072 to 7.342; p=0.036] and co-morbidity with non-communicable disease(s) [AOR, 3.99; 95%CI, 1.604 to 9.916; p=0.003] were independent predictors for poor immunologic restoration (Table 5).

6. DISCUSSIONS

With the successful scale-up of antiretroviral therapy (ART) programs, a life expectancy of people living with HIV (PLWHA) has increased, and HIV is now considered as a chronic disease. There are pieces of evidence that HIV infection and ART are both risk factors for the development of Non-communicable Diseases (NCDs) in resource-limited settings. They suggest that PLWHA benefits from NCD screening and treatment within similar HIV programs [17]. Therefore, this study examined the association of chronic non-communicable disease(s) on HAART outcome, specifically immunologic restoration. To our knowledge, this study provides the first direct comparison of immunologic outcomes among NCD comorbid HIV infected patients and HIV only from Ethiopia. It offers a unique look at the people living with HIV, co-morbid with NCD(s), who are considered to be affected by the double burden of chronic diseases.

Despite insignificant >differencesamong case and control group with regard to baseline socio-demographic, clinical and immunologic characteristics, HIV infected patients co-morbid with non-communicable disease(s) show poor immunologic restoration over 2 years and are high-risk patients for immunologic failure, which paradoxically >negate with theHAART outcomes. As opposed to this study, the report from Cambodia [13], Maryland [14] and Italy [15] showed the good increase of CD4+ cell count (e.g. more than 300% increment of CD4+ cell count among NCD co-morbid PLWHA in Cambodia within 2yrs).This may be related to integrated care of chronic disease in the areas as opposed to the current study area.

Despite early HAART initiation among cases, there were considerable differences in immunologic response over two years from the baseline. >The case groupthough relatively took HAART and lived with HIV for short median duration, >still had poor quantitative restoration of CD4+cell count. And also the average monthly rates of CD4+cell increase were lower among cases. In addition to the direct effect of NCDs on an immunologic response, kinds of literature are supporting the effect of some NCDs in increasing the risk of opportunistic infection like TB. Daniel F-J. et al [16] and Young et al [17] reported that diabetes significantly increases the risk of active tuberculosis, and the co-morbidity is associated with poorer outcomes. So, this has an implication that NCD(s) will pose the patient to develop an opportunistic infection(s), even at high CD4+ cell count.

The current study showed that non-communicable disease(s) was one of the major independent predictors for poor immunologic restoration. The odds of experiencing poor immunologic restoration were 4 times more among NCD(s) comorbid patients. Despite a lack of robust study on NCD(s) effect on the immunologic outcome, different scientific background suggests major challenges of NCD(s) among HIV infected on HAART and also on the HAART-naïve patients. HIV virus has direct effect in inducing inflammations and antiretroviral therapy (ART) regimens indirectly have different effects on patients’ cholesterol and fatty acid balance [18, 19]. In addition, due to the double burden of the diseases, adherence becomes the major factor, which may in turn, affect the HAART outcome. The study from USA [20, 21] and Netherland [22] showed psychiatric comorbidities as the risk factor for HIV disease progression, as it leads to ART discontinuation and/or intermittent HAART utilization.

It appears that certain HIV- associated opportunistic infections disproportionately affect either men or women regardless of the treatment status, which may reflect underlying biological differences between men and women [23]. In this study, though females were dominating in percentage, they had good immunologic restoration as compared to males. In both unadjusted and adjusted analysis, males had significantly higher odds of (more than 3 times) poor immunologic restoration. This study is consistent with the study done in South India [24, 25]. As from the different findings, during the first year after initiating HAART, men experienced a significantly higher incidence of tuberculosis, which also supported the current findings [26]. Nationalized subsidized generic ART and increased antenatal screening will aid women to seek care at an earlier course of the disease and do well in the short term.

It was known that cigarette smoking is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in HIV- negative persons [27] and also is highly prevalent in HIV-positive populations [28]. Likewise, in this study, prevalence of smoking was 27.5%. Though other studies have shown smoking modifies CD4+ lymphocyte counts, but they have been inconsistent in establishing a negative relationship between smoking and the course of HIV/AIDS [29, 30]. The current study revealed smoking as an important independent predictor of poor immunologic restoration. Smokers were approximately 3 times more likely to experience poor immunologic restoration as compared to non-smokers. Similarly, the study from the USA [28, 31], showed a greater risk of virologic rebound and more frequent immunologic failure among smokers. This is secondary to the marked impact of cigarette smoke exposure on the immune system, compromising the host’s ability to mount appropriate immune and inflammatory responses [27]and nicotine’s effect in impairing T-cell proliferation by disrupting the cell’s ability to attach to antigen cells [32]. Smoking may also be linked to biomarkers of HIV disease progression through lower ART adherence. There is evidence that HIV-infected smokers are less adherent to ART medications than HIV-infected nonsmokers [33].

Age was shown to have a significant influence on the probability of poor immunologic restoration on the univariate and multivariate analysis. As from this study, older age was associated with poor immunologic restoration compared to younger counterparts. In fact, most pieces of literature support that older age groups are more likely to have the failure of therapy. This effect of age on immune recovery is due to the associated factor of a decrease in thymic function and other regenerative mechanisms that could impair immune recovery [34]. Viard and colleagues have found the same evidence on a large study conducted to assess the influence of age on immune recovery [35].

Patients who have low baseline CD4+ cell count, especially below the critical CD4+ cell count (<200cells/µL) had a high probability to have poor immunologic restoration. This study is consistent with the study done by Stephen D Lawn and colleagues [36] in three African countries. Since a large proportion of the patients presented very late for treatment with very poor baseline parameters such as low CD4+cell count and late WHO clinical stage, this finding supports the need for a rapid scale-up of counseling and testing for early detection of asymptomatic cases. This will be essential in the prevention of NCD(s), as a risk of co-morbidity occurrence is higher among patients with low CD4+ cell counts [14].

In this study, alcoholic patients had significant odds of poor immunologic restoration as compared to non-drinkers. This study is consistent with the study done by Shacham and colleagues [37]. Moreover, reports of Neblett and colleagues [38] also showed that frequent alcohol use is significantly associated with low CD4+ cell counts. This may be explained as alcohol consumption may increase susceptibility to opportunistic infections and accelerate disease progression among HIV positive individuals. Additionally, alcohol leads to impaired viral load response and reduced CD4+ cell reconstitution [37-39].

Another major predictor of poor immunologic restoration was, living longer with HIV infection. Such observations were also made in other studies [40-42]. The current study showed that living long duration with HIV was associated with poor immunologic restoration. This may be related to persistent immune activation and inflammation from the virus itself and predicts more rapid CD4+ cell decline and progression to AIDS and death [41]. Although immune activation declines with suppressive ART, it often persists at abnormal levels in many HIV-infected individuals maintaining long-term ART-mediated viral suppression even in those with CD4+ cell recovery to normal levels [40, 42].

CONCLUSION

The results of this study indicated that people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA)co-morbid with chronic non-communicable diseases showing poor immunologic restoration and will be suspected as high-risk patients for immunologic failure. Non-communicable diseases slowed the rate of CD4+ T cell recovery at an early period after cART and had negative effects on the kinetics of CD4+cell counts. This study also showed patients with low baseline CD4+ cell counts, underweight patients, those positive for behavioral measures, especially with smoking history, long time on HAART, being HAART naïve for long period and living a long year with HIV were more likely to experience immunological treatment failure. Male sex, smoking, and co-morbidity with a chronic non-communicable disease(s) were found to be independent predictors for immunologic failure among people living with HIV/AIDS.

DEDICATION

This research study is dedicated to our citizens who lost their lives in the ‘’IRREECHAA‘’ festival, the OROMOO's Thanks giving holiday, on Sunday, October, 02/2016 G.C, at Hora Arsadi, Bishoftu, Oromia, Ethiopia.

AUTHOR'S CONTRIBUTIONS

The analysis was conceptualized by TMK, GMI, LCK, and TCE. Data collection was managed by TMK, and data analysis was conducted by TMK with support from LCK, TCE, and GMI. TMK drafted the manuscript. All authors (TMK, GMI, LCK, and TCE) participated in the editing, feedback, and revisions.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

Ethical clearance and approval was obtained from the institutional review board (IRB) of Jimma University, Ethiopia.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

No animals/humans were used for studies that are the basis of this research

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Written informed consent was taken from each study participant after a clear orientation of the study objective.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The data sets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors on request.

FUNDING

This study was funded by Jimma University, Ethiopia with grant number RPGcl/153/2016.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to acknowledge the study participants for their time and dedication to this study and the staff working at TB-HIV follow-up clinic in Jimma University medical center, Ethiopia, for their support during the study. Our deepest heartfelt gratitude also goes to Jimma University for providing grants for this research.

REFERENCES

| [1] | HIV/AIDS JUNPo. Global report: UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic 2010: UNAIDS 2010. |

| [2] | Health FDRoEMo. National Guidelines for Comprehensive HIV Prevention 2014; 1-3. |

| [3] | Evaluation IfHMa. The Global Burden of Disease: Generating Evidence, Guiding Policy 2013; 4-5. |

| [4] | Organization WHO Noncommunicable diseases country profiles 2014. Available at: https://www.who.int/nmh/publications/ncd-profiles- 2014/en/ |

| [5] | Petersen M, Yiannoutsos CT, Justice A, Egger M. Observational research on NCDs in HIV-positive populations: Conceptual and methodological considerations. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 19992014; : 67-01. S8 |

| [6] | Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Ledergerber B, et al. Long-term effectiveness of potent antiretroviral therapy in preventing AIDS and death: A prospective cohort study. Lancet 2005; 366(9483): 378-84. |

| [7] | Deeks SG, Tracy R, Douek DC. Systemic effects of inflammation on health during chronic HIV infection. Immunity 2013; 39(4): 633-45. |

| [8] | Deeks SG, Lewin SR, Havlir DV. The end of AIDS: HIV infection as a chronic disease. Lancet 2013; 382(9903): 1525-33. |

| [9] | Organization WH. STEP wise approach to chronic disease risk factor surveillance (STEPS). Geneva, WHO Available at: http://www.who.int/chp/steps/riskfactor/en/index.html |

| [10] | Riley L, Guthold R, Cowan M, et al. The World Health Organization STEPwise approach to noncommunicable disease risk-factor surveillance: methods, challenges, and opportunities. Am J Public Health 2016; 106(1): 74-8. |

| [11] | Dronda F, Moreno S, Moreno A, Casado JL, Pérez-Elías MJ, Antela A. Long-term outcomes among antiretroviral-naive human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients with small increases in CD4+ cell counts after successful virologic suppression. Clin Infect Dis 2002; 35(8): 1005-9. |

| [12] | Gutiérrez F, Padilla S, Masiá M, et al. Patients’ characteristics and clinical implications of suboptimal CD4 T-Cell gains after 1 year of successful antiretroviral therapy. Curr HIV Res 2008; 6(2): 100-7. |

| [13] | Janssens B, Van Damme W, Raleigh B, et al. Offering integrated care for HIV/AIDS, diabetes and hypertension within chronic disease clinics in Cambodia. Bull World Health Organ 2007; 85(11): 880-5. |

| [14] | Moore RD, Gebo KA, Lucas GM, Keruly JC. Rate of comorbidities not related to HIV infection or AIDS among HIV-infected patients, by CD4 cell count and HAART use status. Clin Infect Dis 2008; 47(8): 1102-4. |

| [15] | Orlando G, Meraviglia P, Cordier L, et al. Antiretroviral treatment and age-related comorbidities in a cohort of older HIV-infected patients. HIV Med 2006; 7(8): 549-57. |

| [16] | Faurholt-Jepsen D, Range N, Praygod G, et al. Diabetes is a risk factor for pulmonary tuberculosis: A case-control study from Mwanza, Tanzania. PLoS One 2011; 6(8)e24215 |

| [17] | Young F, Critchley JA, Johnstone LK, Unwin NC. A review of co-morbidity between infectious and chronic disease in Sub Saharan Africa: TB and diabetes mellitus, HIV and metabolic syndrome, and the impact of globalization. Global Health 2009; 5(1): 9. |

| [18] | Tzur F, Chowers M, Mekori Y, Hershko A. Prevalence of diabetes mellitus among Ethiopian-born HIV patients in Israel. J Int AIDS Soc 2012; 15(6) |

| [19] | de Saint Martin L, Vandhuick O, Guillo P, et al. Premature atherosclerosis in HIV positive patients and cumulated time of exposure to antiretroviral therapy (SHIVA study). Atherosclerosis 2006; 185(2): 361-7. |

| [20] | Carrico AW, Riley ED, Johnson MO, Charlebois ED, Neilands TB, Remien RH, et al. Psychiatric risk factors for HIV disease progression: The role of inconsistent patterns of anti-retroviral therapy utilization Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes 2011; 56(2): 146. |

| [21] | Nurutdinova D, Chrusciel T, Zeringue A, et al. Mental health disorders and the risk of AIDS-defining illness and death in HIV-infected veterans. AIDS 2012; 26(2): 229-34. |

| [22] | Schadé A, van Grootheest G, Smit JH. HIV-infected mental health patients: Characteristics and comparison with HIV-infected patients from the general population and non-infected mental health patients. BMC Psychiatry 2013; 13(1): 35. |

| [23] | Ngwai Y, Odama L. HIV/AIDS prevention services In: Skill certification workshop on HIV 2006; 5 |

| [24] | Kumarasamy N, Solomon S, Flanigan TP, Hemalatha R, Thyagarajan SP, Mayer KH. Natural history of human immunodeficiency virus disease in southern India. Clin Infect Dis 2003; 36(1): 79-85. |

| [25] | Kumarasamy N, Venkatesh KK, Cecelia AJ, et al. Gender-based differences in treatment and outcome among HIV patients in South India. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2008; 17(9): 1471-5. |

| [26] | Kumarasamy N, Chaguturu S, Mayer KH, et al. Incidence of immune reconstitution syndrome in HIV/tuberculosis-coinfected patients after initiation of generic antiretroviral therapy in India. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2004; 37(5): 1574-6. |

| [27] | Stämpfli MR, Anderson GP. How cigarette smoke skews immune responses to promote infection, lung disease and cancer. Nat Rev Immunol 2009; 9(5): 377-84. |

| [28] | Feldman JG, Minkoff H, Schneider MF, et al. Association of cigarette smoking with HIV prognosis among women in the HAART era: A report from the women’s interagency HIV study. Am J Public Health 2006; 96(6): 1060-5. |

| [29] | Royce RA, Winkelstein W Jr. HIV infection, cigarette smoking and CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts: Preliminary results from the San Francisco Men’s Health Study. AIDS 1990; 4(4): 327-33. |

| [30] | Galai N, Park LP, Wesch J, Visscher B, Riddler S, Margolick JB. Effect of smoking on the clinical progression of HIV-1 infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol 1997; 14(5): 451-8. |

| [31] | Hile SJ, Feldman MB, Alexy ER, Irvine MK. Recent tobacco smoking is associated with poor HIV medical outcomes among HIV-infected individuals in New York. AIDS Behav 2016; 20(8): 1722-9. |

| [32] | Kalra R, Singh SP, Savage SM, Finch GL, Sopori ML. Effects of cigarette smoke on immune response: Chronic exposure to cigarette smoke impairs antigen-mediated signaling in T cells and depletes IP3-sensitive Ca(2+) stores. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2000; 293(1): 166-71. |

| [33] | Shuter J, Bernstein SL. Cigarette smoking is an independent predictor of nonadherence in HIV-infected individuals receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy. Nicotine Tob Res 2008; 10(4): 731-6. |

| [34] | Rajasuriar R, Gouillou M, Spelman T, et al. Clinical predictors of immune reconstitution following combination antiretroviral therapy in patients from the Australian HIV Observational Database. PLoS One 2011; 6(6)e20713 |

| [35] | Viard J-P, Mocroft A, Chiesi A, et al. Influence of age on CD4 cell recovery in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy: Evidence from the EuroSIDA study. J Infect Dis 2001; 183(8): 1290-4. |

| [36] | Cantudo-Cuenca MR, Jiménez-Galán R, Almeida-González CV, Morillo-Verdugo R. Concurrent use of comedications reduces adherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected patients. J Manag Care Spec Pharm 2014; 20(8): 844-50. |

| [37] | Shacham E, Agbebi A, Stamm K, Overton ET. Alcohol consumption is associated with poor health in HIV clinic patient population: A behavioral surveillance study. AIDS Behav 2011; 15(1): 209-13. |

| [38] | Neblett RC, Hutton HE, Lau B, McCaul ME, Moore RD, Chander G. Alcohol consumption among HIV-infected women: Impact on time to antiretroviral therapy and survival. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2011; 20(2): 279-86. |

| [39] | Wu ES, Metzger DS, Lynch KG, Douglas SD. Association between alcohol use and HIV viral load Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999) 2011; 56(5): e129. |

| [40] | Lederman MM, Calabrese L, Funderburg NT, et al. Immunologic failure despite suppressive antiretroviral therapy is related to activation and turnover of memory CD4 cells. J Infect Dis 2011; 204(8): 1217-26. |

| [41] | Lederman MM, Funderburg NT, Sekaly RP, Klatt NR, Hunt PW. Residual immune dysregulation syndrome in treated HIV infection. Adv Immunol 2013; 119: 51-83. |

| [42] | Hunt PW, Martin JN, Sinclair E, et al. T cell activation is associated with lower CD4+ T cell gains in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients with sustained viral suppression during antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis 2003; 187(10): 1534-43. |